Gangs and Violence: A Hidden Epidemic

May 7, 2025

Gangs and violence are not just urban problems. They quietly infest small towns, transform neighborhoods, and shatter lives. Most discussions frame gangs and violence through sterile statistics or sensationalized headlines from distant metropolises. What is the truth? Gangs can thrive in small towns too. Santa Paula, California presents a perfect case study. Behind its charming Main Street and scenic mountain views lies what locals have dubbed the “Snake Pit”—a breeding ground where gangs and violence have quietly grown for decades. More precisely, this blog answers two questions: what percentage of gang arrests are for violent acts and what specifically are the violent acts gang members commit.

Jumping-In

The decision to join a gang is a decision to accept violence. When a gang member agrees to be ‘jumped in,’ multiple members beat them for thirteen seconds. To learn why the beating lasts for thirteen seconds see the blog La Eme. When the gang decides to punish a member it is typically with a beating, additional discipline results in more severe violence such as stabbing or even murder.

Gangs are Violence

Gangs operate as violent enterprises—interconnected forces that destabilize communities. At their core, they structure themselves as groups engaged in criminal activities such as drug trafficking, robbery, assault, and murder. They use violence as currency to maintain status, control territory, and enforce loyalty. Beyond financial costs, gangs and violence inflict emotional trauma, loss of life, and shattered community trust.

Let’s Get Into The Numbers Regarding Gangs and Violence

So if you want to understand how gangs are violent, you have to look at the gang members’ criminal records.

In 2014, Santa Paula had five active gangs: the Crimies, 12th Street Locos, Crazy Boyz, Bad Boyz, and Party Boyz, with a total of 211 documented gang members.

I reviewed the criminal histories and categorized the types of arrests for all the gang members. Most importantly, this blog explains what took me weeks to research: the percentage of gang arrests for violent acts, and the specific violent crimes committed.

There Can’t be That Many Arrests

Previously, I had investigated criminals tied to organized crime in Los Angeles, but their arrest records were nothing compared to those of gang members in Santa Paula Forget what television has taught you about gang members. My analysis revealed a very different profile. Santa Paula’s gang members weren’t wayward teenagers. These grown men had established criminal careers, averaging 21 arrests each. Gangs and violence represented their life’s work—not some adolescent phase. In fact, my research showed that between 1978 and 2014, the 211 gang members were arrested more than 4,200 times.

As the gangs grew the frequency increased dramatically over time, from one arrest weekly in 1993 to nearly one daily by 2010. I wanted to dig into those 4,200 arrests and identify how their behavior translated into gangs and violence.

Criminal Charges

My analysis of the 211 gang members’ arrest records revealed 4,276 arrests between 1978 and 2014. Examining these records showed 88% of charges fell into seven categories:

- Drug offenses (25%)

- Violence offenses (21%)

- Property crimes (14%)

- Vehicle offenses (11%)

- Weapons offenses (9%)

- Parole violations (8%)

- Miscellaneous offenses (12%)

The top three categories included drugs offenses, violence offenses, and property crimes. The connection is obvious—drugs generate revenue, violence protects territory, and property crimes get the gang members money to purchase drugs. To learn more read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Some might argue initial arrest charges don’t accurately reflect gang criminal behavior. They’d suggest focusing on convictions instead. I disagree. Arrests provide a more accurate picture than convictions. After defense attorneys negotiate, what a gang member pleads guilty to often bears little resemblance to the crime actually committed. I’ve seen carjackings reduced to “taking a vehicle without consent” and solicitation of prostitution downgraded to disorderly conduct. The arrests tell the true story.

Specific Gangs and Violence Statistics in Santa Paula

The Crimies:

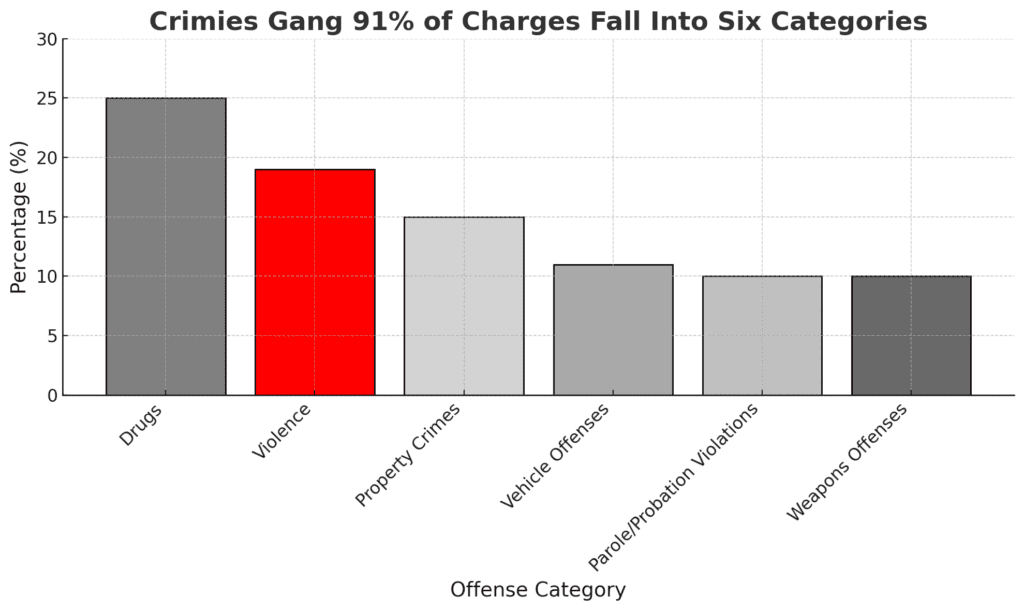

I analyzed the 67 members, their 1530 arrests for 170 different violations and had 2615 charges filed. The number of charges exceeds arrests because police often arrest gang members and charge them with multiple offenses. For example, officers may pull over a gang member for drunk driving. The officers may find the gang member had a gun and methamphetamine. Police arrested the gang member once but charged him with three offenses: drunk driving, illegal possession of a firearm, and possession of methamphetamine

91% of the Crimes’s 2,615 charges fell into six categories: Drug crimes (25%), Violence crimes (19%), Property crimes (15%), Vehicle offenses (11%), Parole/Probation violations (10%), and Weapons offenses (10%).

Below is the breakdown of the Crimies gang violence category charges:

Examining the Crimies violence charges revealed three charges dominated: Obstructing a Public Officer (162 charges), Robbery (59 charges), and Battery (44 charges).

These accounted for 54% of all violence charges against the Crimies gang.

Wife beating was disturbingly common—50 arrests for domestic violence. Gang members rarely faced sex offense charges. One Ventura County gang member told me that other members generally don’t tolerate having an ‘R’—rape—in your criminal history or ‘jacket.’

The 12th Street Locos:

With 59 members, they mirrored the Crimes violent tendencies. Since 1991, they accumulated 1,110 arrests for 180 different violations, resulting in 2,117 charges.

Like the Crimies 19% of the 12th Street Locos charges were for violence offenses.

I did a deep analysis of thirty robberies committed by 12th Street Locos between 1995 and 2013 that revealed their predatory tactics.

Ninety percent of victims were male. Seventy percent of robberies involved multiple gang members. Most telling: 63% of these robberies occurred outside their territory—they actively hunted victims.

Gang members specifically targeted “pisas” (Mexican immigrants who speak little English), knowing these victims rarely report crimes to police. Perfect targets: illegal aliens often carried cash and feared deportation more than they feared the gangs.

A typical robbery scenario: Two 12th Street Locos members approach victims, displaying weapons. “What up ese? Where you from? 12th Street Locos gang!” They demand valuables: “Give up your stuff. If you don’t give us everything in your pockets, we’ll light you up.’ Victims surrender phones and cash, and gang members sometimes beat them anyway. They run a ruthlessly efficient business model built on intimidation and violence.

The Crazy Boyz:

The 41 members of the Crazy Boyz gang accumulated 734 arrests for 159 different violations, resulting in 1,512 charges.

Violence accounted for 20% of their charges, and amazingly, police arrested 37 gang members—90% of the group—for crimes involving violence. Violence crimes included murder, rape, kidnapping, robbery, assault, battery, obstruct public officer, spouse abuse, and child cruelty.

One incident perfectly illustrates the senseless nature of these conflicts. A Crazy Boyz member pulled a gun after a 12th Street Locos member flashed gang signs. The bullets missed their target but struck a nearby woman in her home. She bled to death on her kitchen floor—collateral damage in their idiotic war.

The Bad Boyz

Despite their relatively small membership of 28, since 1990, the Bad Boyz gang accumulated 491 arrests for 136 different violations, resulting in 974 charges.

Unlike other gangs, their primary specialty was violence (25% of all charges), followed by property crimes (19%) and drugs (18%).

A staggering 93% of Bad Boyz members had been arrested for violent crimes, accounting for 239 charges.

The following breaks down categories of violent crimes police arrested the Crazy Boyz for:

3 or 11% were arrested for child cruelty, which accounted for less than 1% or 9 charges;

8 or 29% were arrested for murder, which accounted for less than 1% or 11 charges,

12 or 43% were arrested for spouse abuse, which accounted of 6% or 57 charges and included battery of a spouse and corporal injury of a spouse,

15 or 54% were arrested for robbery, which accounted for 2% or 24 charges.

The Party Boyz:

The Party Boyz represented Santa Paula’s smallest gang with just 16 members. Since 1987, they accumulated 411 arrests for 116 different violations, resulting in 785 charges.

The Party Boyz criminal specialties were drugs (26%), property crimes (26%), and violence (23%).

Their violence was particularly disturbing—94% of members had been arrested for violent crimes (183 charges).

81% for spouse abuse (39 charges).

69% for robbery (32 charges).

25% for murder (11 charges).

To learn more about Santa Paula gangs read the blog Santa Paula Gangs: Mayberry Gone Wrong.

The National Context

Santa Paula is not an anomaly. The stereotype of juvenile offenders getting into fist fights barely scratches the surface of violent crimes these gangs commit. Today’s gang members are older, more sophisticated, and infinitely more dangerous. As demonstrated in Santa Paula, gang members in their thirties and forties remain actively engaged in criminal behavior. Gangs and violence don’t fade with age—they evolve, growing more entrenched and methodical.

Incarceration and Gang Injunctions Solutions to Gangs and Violence

The most lenient citizen would agree that people who are violent need to be incarcerated. Violence defines life in gangs, and their members must be taken into custody to protect the public.

Gang injunctions significantly reduced crime, despite political opposition. Critics often ignore practical realities on the ground where law-abiding citizens desperately seek relief from gangs and violence. To learn more read the blog Laws on Gangs: What Works and What Doesn’t.

Conclusion: Fighting Gangs and Violence

Santa Paula’s “Snake Pit” serves as a powerful reminder of how deeply gangs and violence can embed themselves in even the smallest communities. Through data analysis, interviews, and direct observation, the hidden epidemic reveals itself: People who join a gang are committing themselves to a lifestyle of violence.

Understanding the reality of gangs—their evolution, structure, and devastating impact—represents the first step toward community reclamation. Wishful thinking won’t solve this crisis. We must confront the dark reality of gangs and violence with clear-eyed determination, knowing that ignorance only fertilizes their growth.

To learn more about gangs and violence, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.