Southside Chiques: A Violent Neighborhood

May 23, 2025

In 2019, the Southside Chiques gang consisted of approximately 171 members. Collectively the gang had been arrested 3,458 times. That’s an average of 20 arrests per gang member. Authorities had arrested one gang member 76 times.

Let’s pause there. Seventy-six arrests. That’s not petty theft and graffiti. Obviously that’s chronic criminal behavior and repeated disregard for the law.

Of the 171 gang members:

- 124 had felony convictions (73%)

- 94 had been to prison (54%)

- 40 were on probation or parole (23%)

- 43 were in state or federal custody (25%)

These aren’t just troubled youth. They are committed criminals. And they all wear the same badge: Southside Chiques. To see where Southside Chiques ranks read the blog Top 10 Most Dangerous Gangs in Ventura County.

Southside Chiques: The Economic Impact

Each Southside Chiques arrest costs taxpayers—on the low end—about $1,000. Surprisingly that’s $3,458,000 spent just on booking and processing this one gang. And that doesn’t include court costs, public defenders, parole, or probation.

A total of 40 or 23% of the gang members were on probation and/or parole. To supervise someone on parole costs about $10,000 per year. Comparatively, to supervise a person on probation costs $4,400 per year. If half the Southside Chiques gang members were on parole and the other half of the members were on probation, that totals $288,000 in supervision costs each year for California (parole) and the County of Ventura (probation). Even if you don’t live in the city of Oxnard, but you live in California you are paying to supervise the Southside Chiques gang.

How Much Does it Cost to Incarcerate the Southside Chiques Gang?

Each time a Southside Chiques member enters the prison system, taxpayers foot the bill. The average incarceration cost per inmate in California is $81,000 per year. With 43 Southside Chiques members in custody, that’s about $3.5 million annually—just to house them. Some members are in federal custody, so even if you don’t live in the state of California, you are paying to house Southside Chiques gang members.

Finally, when you add up arrests, probation/parole, and incarceration, the Southside Chiques gang costs taxpayers over $4 million every year.

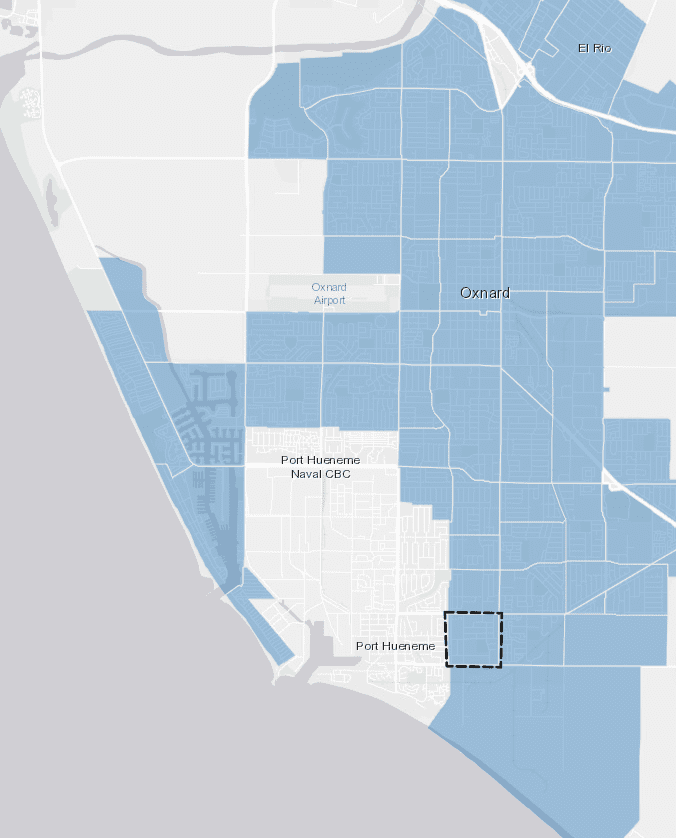

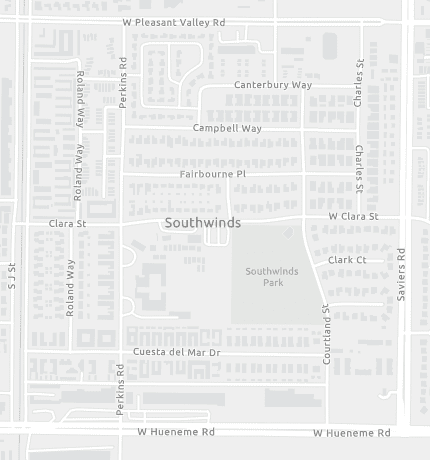

Southside of the City, Center of the Problem

The Southside Chiques gang derives its name from the southern side of Oxnard, California. The gang have claimed their section of the city. Four key streets carve their territory into Oxnard’s grid: East of J Street, South of Pleasant Valley Road, West of Saviers Road, and North of Hueneme Road. This area has become synonymous with shootings, narcotics, carjackings, and arrests.

Where Did the Name Chiques Come From?

Chiques is the name gang members have bestowed on the city of Oxnard. I’ve heard two origin stories for the name “Chiques.” The first was that crime got so bad in the Colonia neighborhood in Oxnard that the people began to describe it as “little Chicago,” which morphed by the Spanish speakers from “chiquis or little ones” which became the name Chiques. Another version was the marijuana trade extended from Oxnard to Mexican/Americans in Chicago. People often referred to Chicago’s organized crime as the Chicago Outfit. Drug smugglers in Oxnard claimed they were part of or “little members” of the “outfit” which became known as Chiques. One thing I know for sure is if you ask any Oxnard gang member the origin of the name Chiques, they will have no idea.

To learn more about Oxnard gangs see the blog Oxnard Colonia Chiques.

Southside Chiques Gang Names

Typically, a gang member receives their gang name based on a personality trait, physical characteristic, behavior, or reputation. The following is a list of some of the monikers or gang names of Southside Chiques gang members: Animal, Bones, Capone, Casper, Ceeno, Chops, Creeps, Cricket, Danger, Daffy, Drifter, Fatal, Gangster, Ghost, Goofy, Gunner, Happy, Lil Bear, Lil Crazy, Loko, Maniac, Mute, Nacho, Neto, Night Owl, Nutty, Psycho, Racoon, Rascal, Reaper, Rowdy, Soldier, Smash, Smokey, Sneaks, Stoney, Tank, Tubs, and Venom. To learn more read the blog Gang Names: Understanding the Criminal Identity System.

Southside Chiques monikers for female gang members include Coneja, Diabla, Green Eyes, and Star. To learn more about female gang members read the blog Gang Initiation for Females: The Untold Reality Behind the Drama.

Southside Chiques Clothing

Unlike some gangs that only tag walls or make noise on social media, the Southside Chiques live a violent lifestyle. The gang etches their identity into every corner, every street sign, and every police report. Their chosen uniform—Chicago White Sox apparel—isn’t a fashion statement. The “S” in “Sox” stands for “Southside,” and they wear it proudly.

It’s more than a street gang—it’s part of a broader Hispanic gang network in Southern California heavily influenced by the prison gang known as the Mexican Mafia, or “La Eme.” To learn more about the Mexican Mafia see the blog La Eme.

This gang hierarchy allows senior members behind bars to direct criminal activity in neighborhoods like Southside Oxnard, where the Southside Chiques act as enforcers and drug traffickers. To learn more about other Oxnard gang read the blog Gangs and Ghost Guns: The Deadly Intersection of the Loma Flats Gang and Law Enforcement.

Southside Chiques Gang Injunction: Critics vs Reality

The Southside Chiques were subject to a civil gang injunction a year after the Colonia Chiques gang injunction. Like the first, it banned gang members from congregating in public, wearing gang clothing, flashing signs, and intimidating residents. That injunction ended in 2021—nevertheless, during its enforcement, crime dropped.

Critics of the injunctions, including some lawyers and activists, complained the orders violated civil liberties. What they didn’t offer were solutions. Meanwhile, the gang injunction’s discontinuation harmed the people actually living in Southside Chiques territory.

Every law enforcement officer I spoke to, supported the injunctions. Why? Because they worked. Gangs had fewer places to gather. Less intimidation and assaults, fewer shootings. The injunctions gave the community room to breathe. The lawyers who pushed for discontinuing the gang injunction don’t live in the Southside of Oxnard.

Did the Southside Chiques Gang Injunction Work?

A reasonable question is did the gang injunction increase public safety? To answer that question, law enforcement only had to look at the criminal histories of the 66 Southside Chiques gang members who were listed in the injunction. Obviously, each arrest of a listed gang member following the gang injunction’s termination proved the community was less safe.

Let’s estimate that police arrested those 66 Southside Chiques gang members twice since the injunction ended in 2021—that’s 132 arrests. Based on my analysis of over 4276 arrests, of the Hispanic Santa Paula gangs, 88% of their arrests fell into seven categories:

- Drug offenses (25%) 33

- Violence offenses (21%) 28

- Property crimes (14%) 18

- Vehicle offenses (11%) 14

- Weapons offenses (9%) 12

- Parole violations (8%) 10

- Miscellaneous offenses (12%) 16

To learn more about Santa Paula gangs see the blog Santa Paula Gangs: Mayberry Gone Wrong.

The math is simple: 132 preventable crimes means 132 victims who paid the price for ideological opposition to proven gang suppression tactics. To learn more about the violent crimes gangs commit see the blog Gangs and Violence.

Technology Helping to Hold Southside Chiques Accountable

In 2018, a police body cam recorded a foot chase in Southside Chiques territory. Caught on camera during the pursuit, the gang member threw a dark object down on the ground near a fast food restaurant. Later during the recorded chase, the gang member threw a plastic baggie just as the officer caught and tackled the suspect.

Then, moments later the officer retrieved the baggie with drugs. The officer walked back toward the fast food restaurant; there lying on the ground was a loaded semi-automatic handgun.

The gang member had thrown a loaded .45 from his waistband. Police also found that he had over 10 grams of methamphetamine. The gang member’s actions demonstrated a complete disregard for other people. Worse yet, what if a kid had picked up the gun or taken the drugs?

Without the body worn camera a persuasive defense attorney could argue the officer did not see the drugs or gun being thrown. Predictably, the attorney would try to create doubt particularly if the attorney could trip the officer up when reviewing the officer’s report or on the witness stand.

Adopting the Case Federally

Fortunately, the camera captured the entire incident. Officers could slow down or stop the images, and everyone could see the gun flying from the gang member’s hand. This irrefutable video evidence led federal authorities to adopt the case, much to the gang member’s fear.

Seventeen arrests. Three felonies. A loaded gun and narcotics. The gang member was looking at 15 years in federal custody for having the gun and drugs. In the end, the federal prosecutor agreed to drop the gun charge if he pleaded guilty to the drugs. The gang member got 92 months. That’s 7 ½ years in prison.

What Happens Next for Southside Chiques?

The reality is, Southside Chiques won’t disappear because we wish them away. They’ll disappear when the public demands real accountability through incarceration.

Until then, Southside Chiques will continue to recruit, rob, and kill. They sell drugs, enforce territory through violence, and maintain loyalty through fear. Today, their presence in Oxnard is deeply entrenched—and despite periodic police crackdowns and arrests, the gang persists. To learn more read the blog Northside vs Southside Gangs in Oxnard: History and Violence.

Clearly, the story of the Southside Chiques is more than a local problem. It’s part of a larger pattern across California, where prison gangs extend their reach into Hispanic communities, using young men as pawns to make money in a larger criminal enterprise which results in drug addiction, violence, and death.

To learn more about Southside Chiques and other gangs in Oxnard, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.