Hispanic Gangs: Inside The Dirty Nickel

May 28, 2025

The picturesque landscapes of Ventura County hides a troubling reality, beneath the surface where Hispanic gangs operate with surprising persistence. I’ve spent years investigating these groups, and the patterns remain disturbingly consistent. To learn more read the blog Top 10 Most Dangerous Gangs in Ventura County.

The Invisible Problem

In 1988, when gang violence spilled into Westwood near University of California Los Angeles, the media suddenly “discovered” gangs. Funny how proximity to wealth changes perception. For decades before that, South-Central Los Angeles suffered from gang violence without significant attention. The same pattern emerged in Ventura County, where officials tolerated Hispanic gangs as long as the violence remained contained within certain neighborhoods.

Gang members often referred to Ventura County as the “dirty nickel” – a reference to the 805 area code and the ugliness lurking behind its polished façade. Visitors often comment that Ventura County has a great climate and represents peace and beauty. The view from inside juvenile halls and jail cells revealed something entirely different: Hispanic gangs recognized an alternate worlds of crime, drug use, and self-destruction.

The Demographics Are Clear

In 2014, the Santa Paula Police Department shared gang photographs with me. A pattern emerged immediately. Most Hispanic gangs consisted of young adult Mexican-American males, often related to each other, many already tattooed with symbols of lifelong allegiance. Similar images from other local law enforcement in 2016 and 2018, of other towns and cities in Ventura County confirmed the same demographic makeup. Over 1,500 young men in Ventura County chose to join Hispanic gangs—in other words a choice that destroys their future.

To learn more about Ventura County gangs read the blogs Oxnard Colonia Chiques, Southside Chiques: A Violent Neighborhood, and Santa Paula Gangs: Mayberry Gone Wrong.

The FBI’s 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment revealed about 48% of community crime stemmed from gang activity. In cities like Santa Paula and Oxnard, Hispanic gangs dominate this landscape almost exclusively. Let’s be clear: these aren’t multi-racial crews uniting against systemic oppression. They’re Mexican-Americans fighting other Mexican-Americans over respect, drug territory, or forgotten insults.

A gang member pulled a gun and forced his rival to choose: stomp on his own gang hat or take a bullet. It’s a form of psychological torture designed to be more devastating than just physical violence. Making someone destroy their own gang colors is about breaking their spirit, not just their body. The gun ensures compliance, but the real weapon is the humiliation.

What Makes Hispanic Gangs Different

What separates Hispanic gangs from other criminal groups is their:

Continued participation as members age.

- Intergenerational nature.

- Integration with prison gangs.

- Immigration status.

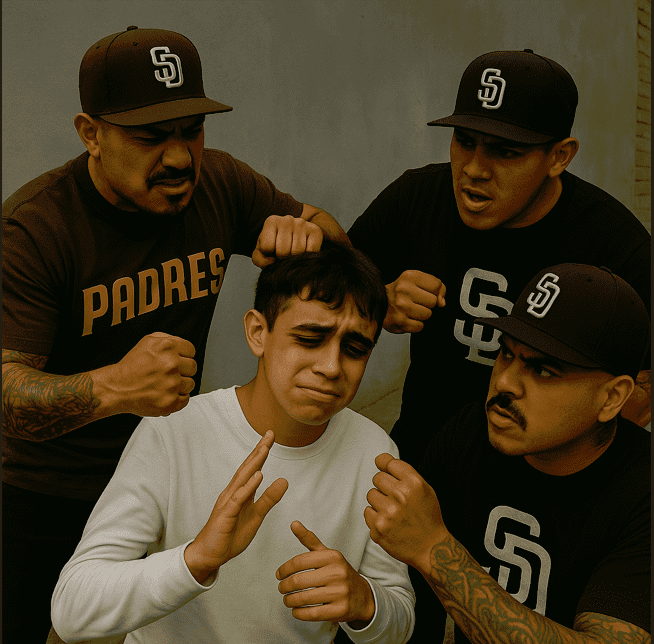

Many gang members I interviewed had fathers, uncles, or brothers in the same organization. Recruitment often began in junior high school. I’ve seen sons proudly follow their fathers’ footsteps into the gang lifestyle, sometimes with paternal help during initiation rituals.

But why? What draws these young men toward Hispanic gangs rather than education, employment, or community service?

Most Hispanic gang members are United States citizens, however their parents are from Mexico, have little education, and do manual labor.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance report “Police Response to Gangs: A Multi-Site Study and Gang Structures, Gang Patterns, and Police Response and A Practical Guide,” back in 2004, asked members of the community, including law enforcement officials, why gangs exist? “The acknowledgement that gang membership in Hispanic community was disproportionate and was explained by the following participant: I think Hispanic culture, as it has existed throughout the last few generations, has kind of prompted a lot of this sense of “we kind of all need to draw together.” The neighborhood kind of need to protect themselves.” “An Albuquerque officer explained the old Hispanic gangs have existed there for years. They’re fighting with each other.”

The Root Causes

One explanation lies in the theory of “Differential Opportunity.” When legal paths to success appear blocked – through poverty, parental neglect, or poor performance in school – alternative routes emerge. Hispanic gangs provide status, identity, belonging. Yet many members admitted that nothing about gang life made them feel “successful” – only wanted.

This aligns with what economists Steve Levitt and Stephen Dubner explained in their book “Freakonomics“: growing up in poverty, single-parent homes, or with teenage mothers significantly increases the likelihood of criminal behavior. In Santa Paula, 22% of children live below the poverty line, and 20% of families have only one parent. With a Hispanic population of 80%, these risk factors concentrate heavily in one demographic.

Could abortion laws affect gang membership? “Freakonomics” argued that legalized abortion indirectly reduced crime by preventing unwanted children from entering neglectful environments. In Hispanic communities, where religious beliefs often oppose abortion, this “safety valve” never opened. The Guttmacher Institute reports that Hispanic women obtain only 25% of abortions, despite their high poverty rates. Hispanic women have lower abortion rates than White and Black women. What if unwanted pregnancies lead to future Hispanic gangs membership?

“We Felt Unwanted” — Voices from the Street

This isn’t mere theory. Ventura County gang members repeatedly told me: they felt unwanted. Their parents worked constantly. Fathers were absent. Mothers were exhausted. They turned to Hispanic gangs for belonging that school and family withheld. I’ve never interviewed a gang member who told me he came from a supportive family, with two parents, in a loving home.

A few years ago the country of El Salvador has the toughest anti-abortion laws in the world and a disproportionate number of gang members. El Salvador, once known for having the highest crime rate in Central America, faced staggering violence largely attributed to its 60,000 gang members. According to the U.S. Department of State, the country was ranked as one of the most violent in the world.

When Youth Typically Join Hispanic Gangs

Most joined between ages 11 and 16. The gang initiation ritual is called “jumping in” – or enduring a 13-second beating as initiation. Others were “crimed in” – tasked with committing burglary or theft. Regardless of entry method, the results remained tragically consistent: drug use, criminal activity, incarceration. All volunteered. None were forced to enter the gang life. To learn more about gang initiation see the blog Why People Join Gangs?

Hispanic gangs maintain strict internal codes that appeal to youth seeking structure. Don’t snitch. Pursuing another member’s girlfriend is strongly discouraged. Don’t start conflicts around children. Violating these rules typically results in physical punishment. For teenagers from chaotic households, these predictable rules feel like stability. When rivalries develop between Hispanic gangs, members rarely know the original cause – they simply understand they’re supposed to hate the other Hispanic gang. To learn more read the blog Inside Gang Culture: Rules and Rituals.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here’s an ugly reality that demands acknowledgment: most members of Hispanic gangs harbor deeply racist attitudes. I’ve monitored wiretaps, reviewed text messages, and conducted interviews where Ventura County gang members freely used racial slurs, particularly against Black people. In prison, these tensions erupt into race riots. While some Hispanic gangs might accept White members – especially those with Mexican heritage – they view Black inmates as inferior enemies.

People who join gangs rarely display intellectual depth. The decision to join typically stems from impulse rather than careful consideration. It’s difficult to label someone a “victim of circumstance” when they embrace self-destruction so willingly. Let’s be honest – joining these groups represents poor decision-making, further amplified by drug use. They are confusing recklessness with masculinity.

Obviously most Mexican-Americans males do not follow this destructive path. They value education, work diligently, and build fulfilling lives. But those who choose Hispanic gangs represent a distinct subset – more similar to impoverished white drug users than to immigrant success stories. Four characteristics all gang members embody is the acronym DRIP: Druggy, Racist, Idiotic, Poor.

The Daily Reality

Their living conditions tell another story. Homes are filthy. Rooms disorganized. Yet their clothing – ironically – remains clean and coordinated, often displaying sports logos or gang colors. They care more about the appearance of having success than of being truly successful.

One element binds nearly all Hispanic Gangs: drugs. Marijuana, heroin, fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine – they use and sell it. Substance abuse provide an escape from their childhoods. Drug use also creates a self-perpetuating cycle of poverty and crime. Gang members steal and rob to fund their addiction. They get arrested. Ultimately they serve time. The pattern repeats endlessly. To learn more about the relationship between drugs, property crimes, and violence see the blog Gangs and Violence.

A strange silver lining? Their drug use prevents effective organization. Imagine if hundreds of young men were sober, trained, and unified. They would overwhelm law enforcement. Instead, they’re too intoxicated to organize effectively – too disoriented to think beyond immediate gratification.

This doesn’t render them harmless. These same young men riot in prisons, traffic narcotics, and terrorize neighborhoods. They may lack strategic vision, but they remain dangerous. To learn more read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Organization Level

Previous researchers suggested Hispanic gangs lack organization in drug distribution. I disagree, particularly in today’s digital landscape. In Ventura County, gang members constantly communicate through, phone, text messages, and social media to sell drugs, coordinate crimes, or develop new supply sources. The notion of disorganized groups who occasionally distribute drugs belongs to a bygone era.

How Many Illegal Aliens are in Hispanic Gangs

Often people wonder how many illegal aliens are in Hispanic gangs? In 2014, there were 211 documented gang members in Santa Paula. I identified 13 or 6% who were illegally in the United States. In 2019, when I analyzed the 1107 gang members in Oxnard, I found again 6% were illegally in the United States.

Most Hispanic gangs have members who are illegal aliens. Four of the five Santa Paula gangs had members who did not have an immigration status. The gang with the highest percentage of illegal aliens in Ventura County was the Thousand Oaks gang the Tocas, 22% (14 members out of 68) of the gang were illegally residing in the United States.

There are approximately 1,500 Hispanic gang members in Ventura County, approximately 6% or 90 are illegally in the United States.

A misrepresentation often claimed is illegal aliens do not commit as many crimes as US citizens. After 2017, the state of California restricted law enforcement and became a sanctuary state. Prior to 2017, illegal aliens who were arrested were deported. Being deported was the reason why they did not go on to commit more crimes not because they were leading lawful lives.

Solutions That Might Work Combating Hispanic Gangs

We must start by accepting reality: these youths join Hispanic gangs voluntarily. They aren’t victims in the legal sense. These young men make poor choices that society pays for through higher taxes, increased policing costs, and overcrowded prisons.

Could early intervention help? Perhaps. But even skilled counselors struggle to counteract years of feeling unwanted.

Could expanded abortion access reduce future crime? Possibly, but that introduces political complications. One certainty remains: schools cannot correct parental failures. To learn more read the blog What to Do About Gangs: A Street-Level Perspective.

The harsh truth is this: Hispanic gangs aren’t merely symptoms – they represent choices. Destructive, generational, self-perpetuating choices made by boys who crave belonging more than success.

The government of El Salvador implemented a series of tough anti-gang policies that drastically reduced crime. This included declaring a state of emergency, mass arrests, and incarceration. The country’s crackdown on gangs led to a sharp decline in violent crime, including homicides.

As we consider solutions, we must balance compassion with accountability. California has a higher ratio of gang members than 90% of the United States. Unfortunately, for now the “dirty nickel” will keep claiming more lives.

To learn more about Hispanic gangs, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.