Roles in Gangs: How Power and Profit Shape Street Culture

July 23, 2025

Roles in gangs define everything from who gives orders to who carries the product. When outsiders look at a gang, they see chaos. Gang investigators see structure. Mapping those roles is the first step to understanding how a seemingly loose assortment of criminals can survive police raids, internal feuds, and prison sentences.

My years working gang cases in Southern California taught me one truth: hierarchy, not randomness, keeps these groups alive. Every cooperator I interviewed eventually circled back to roles in gangs. Who’s the shot-caller? Who’s an enforcer? Who controls the money? These aren’t casual questions. They’re the blueprint for everything that follows.

Belonging Before Business

Sociologists debate whether gangs start for economic gain or social identity, but field experience suggests identity comes first. Young people—mostly males—search for belonging, and roles in gangs offer ready-made status ladders. Interestingly sometimes discipline is what the young men are craving and an immediate beat down for getting out of line satisfies a phycological need from their chaotic home lives. To learn more about gang initiation see the blog Gang Initiation Fight: Understanding the Brutal Gateway to Gang Life.

Once each member accepts his slot in the structure, social bonds harden into profit-driven crime. To learn more read the blog Why Do People Join Gangs?

Original Gangsters: The Corporate Chairmen

People give titles to leaders. In gangs, members call their leaders ‘OG’ for original gangster or ‘shot caller.’ Younger members look up to them because their reputations already shine. Their stature within the roles in gangs matrix is mentorship and arbitration, not daily violence. They settle disputes, call meetings, approve retaliation, and teach younger members how to survive gang and street politics.

Gangs hold meetings to settle disputes between their members. Occasionally, leaders of the gangs would meet to settle disputes between gang members. I spoke with a Ventura County gang leader, and he told me often gang leaders would try to meet, but as a group they were unreliable and some would not show up for meetings.

In prison, the prison gang Eme or Mexican Mafia members are the leaders/shot callers. Eme associates learn early that questioning orders leads to beating, shunning, or worse. I debriefed a Sureno (a Southern California gang member in prison) who explained, ‘If you’re told to handle that, you handle it—period.’ He understood the brutal clarity of roles in gangs: disobedience equals treason, and if your lucky you will just receive a beating.

Members/Soldiers: The Action Arm

Directly beneath Leaders/OGs are the soldiers or gang members. The military rejects most gang members because of their criminal histories and drug use. Their slot in the roles in gangs ecosystem is pure action: shootings, drug runs, and witness intimidation. To learn more see the blog Gangs and Violence.

The jail-house “checking” ritual illustrates this perfectly. One Ventura County gang member took his beating from other Hispanic gang members, refused to cooperate with deputies, and emerged with elevated status.

The only thing that saves society from these large groups of fighting aged males is their drug use. Intoxication and unreliability explains why they can’t keep a job. Drug abuse prevents gangs from completely taking over communities.

Women at the Margins—Couriers and Lookouts

Female participation rarely exceeds single digits, yet their roles in gangs are strategic. Women carry pistols in diaper bags, mule heroin under bus seats, and livestream court testimony to expose “rats.” Undeniably, sexism limits their roles; however, they observe who the ‘shot callers’ are and provide a wealth of information. To learn more see the blog Gang Initiation for Females: The Untold Reality Behind the Drama.

Children—Both Camouflage and Currency

Nothing disarmed a police search faster than terrified kids. A Los Angeles drug dealer coached his nine- and eleven-year-old daughters to scream whenever agents approached the kitchen sink, the exact hiding spot for methamphetamine. Leveraging children is a grim but effective tactic embedded in roles in gangs, turning family into living shields.

Elsewhere, I watched a Santa Paula gang father juggle backpack-carrying offspring from six different mothers—evidence that prolific breeding can double as welfare fraud and street legend. Those youngsters often become future recruits, proving how roles in gangs can span generations.

Prison: If You Offend the Wrong Person it Could End Your Life

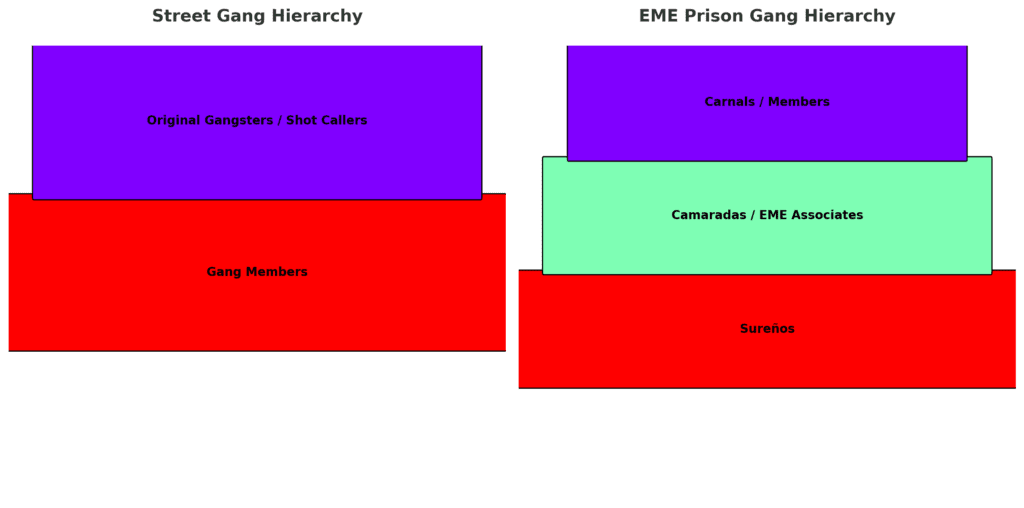

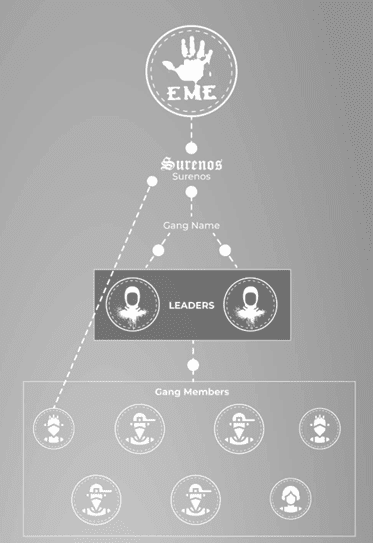

Inside California prisons, the prison gang the Mexican Mafia also known as “Eme” refines roles in gangs with corporate precision. Full members carnals/brothers, also called tios/uncles sit at the apex, divisional shot-callers run yards, and hand-picked EME associates enforce edicts among rank-and-file Surenos (Southern California gang members).

Gang members call EME associates Camaradas, sobrinos (nephews), or camarones (shrimps). Leaders lecture them on the rules—don’t be a rat, coward, or homosexual—and distribute those rules like employee manuals. Below the Eme associates are the Surenos or Southern California gang members. To learn more about prison gangs see the blog La Eme.

Eme associates rise only after three EME members vote them in, mirroring a board-of-directors scheme. Accordingly, failure to follow orders triggers beatings, shunning, or a “green light”/death—sanctions harsher than any corporate HR department. By the time a street soldier returns home, prison-honed roles in gangs follow him, magnifying both his stature and the gang’s reach.

Discipline as Daily Routine

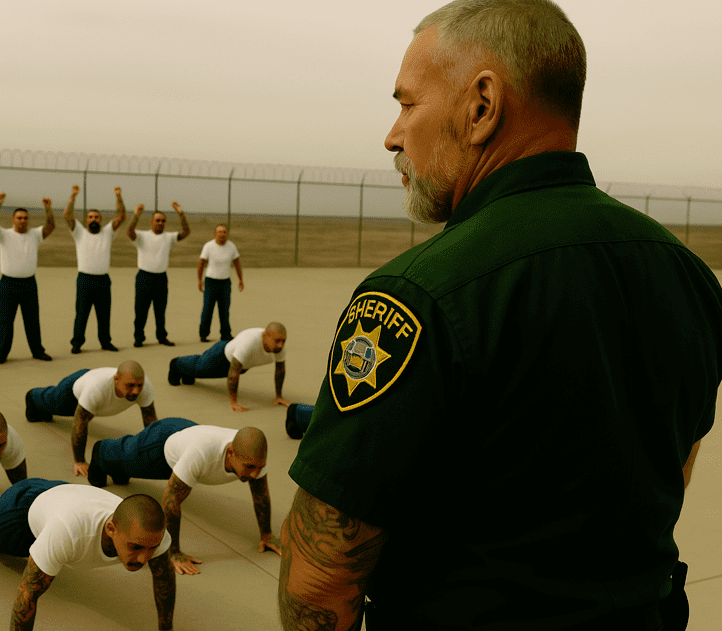

Exercise in prison mandated (burpees, Aztecs, running before dawn) serve dual purposes in prison: fitness and obedience. Moreover, when an EME associate shouts cadence, everyone moves. That ritual engrains roles in gangs through muscle memory—an incarcerated form of boot camp.

Communication mirrors espionage: Nahuatl phrases, folded “kites,” and slang like “hard candy” (kill order) or “red light” (hands off). These codes establish who can speak, who must listen, and who dies next. Eme members cannot politic (talk behind members back to influence other members). Discipline preserves structure; without it, roles in gangs would fracture under the weight of paranoia and punishment.

In the Thousands

In 2020, within the federal prison system, there were an estimated 57 validated EME members and 3538 Surenos.

Within the California prison system, there are approximately 182 validated EME members and 2,189 EME associates, and thousands of Surenos. Interestingly, there were approximately 654 prison gang drop outs who have been debriefed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, and have provided a plethora of information about the roles in gangs.

Money Flow—the Business Model

Drug street distributions mimic franchise operations. Local drug sellers owe a 30 percent “tax” to EME middle-men, who route the cash “upstate.” That steady revenue bankrolls commissary deposits, attorney fees, and bribes. On the contrary, if the tax isn’t paid and your a drug dealer expect to get a beat down once you enter prison. To learn more about gangs and drugs see the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Profit is not random—it’s assigned through roles in gangs: OGs set territorial “rent,” soldiers enforce it, females smuggle product, and juveniles act as runners. Ultimately, the machine stalls only when those roles are disrupted simultaneously.

Intelligence Charts—Seeing Is Believing

Generally, most people are visual learners; therefore, gang charts help map out a criminal enterprise. Leaders up top, links to EME, alphabetical rows for every member, with their true name and moniker, with tags like “FELON.” To learn more see the blog What to Do About Gangs: A Street-Level Perspective.

Conclusion—Clarity Before Conquest

Whether on a street corner in Oxnard, a cell block in Tehachapi, or a courthouse gallery in Ventura, roles in gangs dictate who gives the orders and who is placed to gather the best information.

Roles in gangs will keep adapting—because every vacuum in power, profit, or protection invites a new recruit eager to fill the role left empty.

One of the first steps to understand a gang is to figure out the roles in gangs.

To learn more about roles in gangs, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.