Inside Gang Culture: Rules and Rituals

August 6, 2025

When most people think of gangs they don’t think of gang culture. They picture street violence, tattoos, and hand signs. But beneath the surface lies an intricate web of rituals, rules, and hierarchies that shape every facet of gang life. Culture refers to the shared beliefs, values, and social behaviors of a particular group of people, often encompassing their way of life, including traditions, and artistic expressions. From the streets of Ventura County to the prison yards of California, gang culture is more than just criminal behavior—it’s a code of identity and misplaced loyalty.

Rules That Govern the Streets

One of the universal truths of gang culture is this: do not cooperate with law enforcement. Snitching is the cardinal sin, and those who violate this rule pay a steep price. In Ventura County, for example, members of the 12th Street Locos operate under a loosely defined, but strictly enforced, set of rules. Cooperation with the police can lead to beatings, targeting of family members, and even death.

Another common rule in gang culture is personal loyalty—particularly when it comes to relationships. Having sex with another gang member’s girlfriend or wife is off-limits. Violence is regulated too; members are discouraged from attacking rivals in front of children or families. Violate these codes, and expect a “beat down” by fellow members. These aren’t suggestions—they’re gang rules wrapped in a twisted sense of honor.

Disputes are often resolved in gang meetings. Sometimes gang leaders will meet with others to settle feuds, but as one Ventura County gang leader told me, reliability is rare. Even when leaders attempt diplomacy, attendance is inconsistent. Gang culture operates on brutality and fear.

Hispanic Culture

The Bureau of Justice Assistance asked members of the community, including law enforcement officials, why gangs exist. “The acknowledgement that gang membership in Hispanic community was disproportionate and was explained by one participant: I think Hispanic culture, as it has existed throughout the last few generations, has kind of prompted a lot of this sense of “we kind of all need to draw together.” The neighborhood kind of need to protect themselves.” “An Albuquerque officer explained the old Hispanic gangs have existed there for years. They’re fighting with each other.”

From Streets to Cells: Where Gang Culture Intensifies

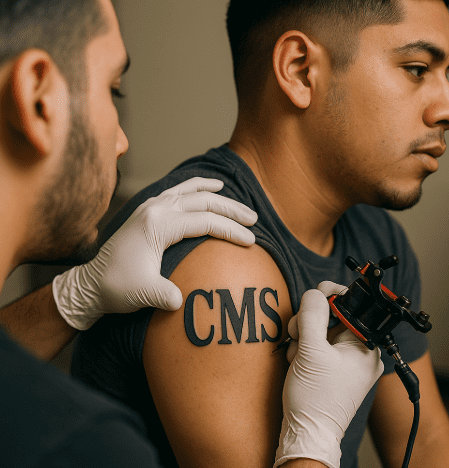

Once a gang member lands in prison, the rules don’t fade—they intensify. In California prisons, Hispanic inmates from Southern California gangs are automatically categorized as Surenos. Even if they were rivals on the outside, prison politics demand unity. The color blue, tattoos like “SUR,” “X3,” and Aztec imagery mark their identity.

Surenos operate under the direction of the prison gang the Mexican Mafia, or EME, the prison’s apex gang. The letter “M” is the 13th in the alphabet—hence the obsession with “13” in tattoos and rituals. Getting “jumped in” to a gang often involves a 13-second beating—a tribute to EME. To learn more read the blog Why Do People Join Gangs?

In gang culture, tribalism is on full display in prison yards. Race defines prison gang culture absolutely. Race defines alliances. If you are half white and half Mexican you don’t qualify as a Sureno. Hispanic inmates cluster with other Surenos. Northern California inmates—Nortenos—are the enemy. The border between North and South has shifted over the years, from Bakersfield to San Jose, but the underlying segregation remains constant.

The EME Hierarchy: Gang Culture’s Corporate Structure

Within EME, structure is everything. At the top are full members—carnals or “Big Homies.” Below them are associates, known as Camaradas or “shrimps.” These EME associates are not just honorary titles—they are soldiers expected to kill, enforce rules, and maintain discipline.

To become an EME member, one must be male, Hispanic, and from Southern California. The nomination process is strict: three votes from EME members are required. If someone falsely claims EME ties, the punishment is death. To learn more read the blog La Eme.

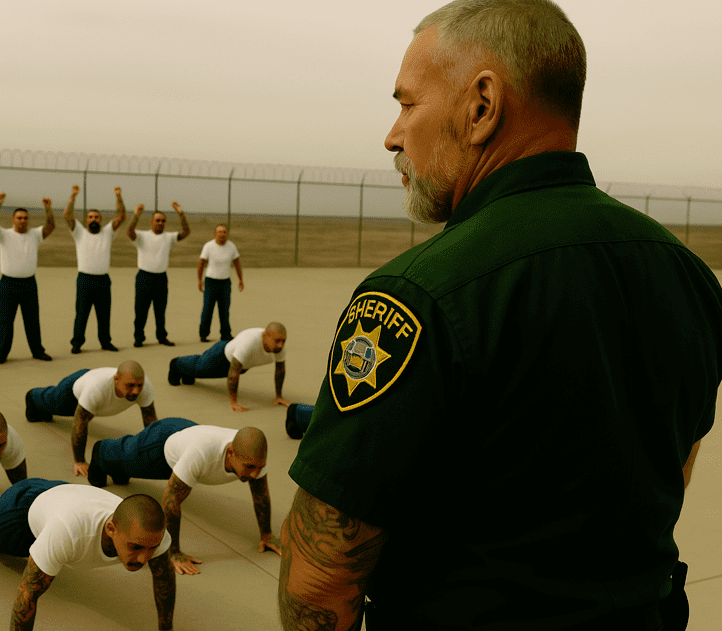

Gang culture here is formalized. EME rules are written and distributed to associates. Wake up before 5:30 a.m., no sleeping during the day (unless your cellmate is awake), never disrespect a member, and—of course—never cooperate with guards or law enforcement.

Physical discipline is key. Associates are required to do exercises—pushups, burpees, Aztecs, leg lifts—on command. Failure to comply means punishment. A first offense results in a beating. A second results in shunning—total social isolation. According to one associate, “You are alone, and you don’t want to be alone in prison.” Third strike? Stabbing or death.

The Psychology of Belonging

What makes gang culture so appealing, even with its brutality? It offers identity and acceptance. The people drawn to gangs often come from broken homes and neglect. One Ventura County gang member explained that drug use helped numb the pain of his childhood. He started using at 15, committed crimes to fund his habit, and soon found himself incarcerated.

Drugs and gangs are intertwined. In Ventura County, the gang members I encountered used marijuana, pills, heroin, fentanyl, and methamphetamine. Ironically, this widespread drug use may be what prevents gangs from becoming more organized and dangerous. Imagine if these men—outnumbering police 100 to 1—were sober, strategic, and unified. Instead, gang culture is intertwined with addiction. To learn more read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underworld Economy of Crime.

DRIP: A Profile of Ventura County Gangs

My research revealed consistent patterns in gang culture membership. In my experience, Ventura County gang members fit the profile, summed up by the acronym DRIP:

- Druggy

- Racist

- Idiotic

- Poor

Gang members are invariably drug users. They are openly racist, especially against Black people. In prison, most racial riots involve Hispanic and Black inmates. The use of racial slurs is common, even among gang members toward each other.

Their behavior is often self-destructive. Joining a gang is idiotic—but these men continue despite beatings, stabbings, and shootings. I’ve seen gang members proudly protect a crummy street that looks more like a war zone than a neighborhood. And even after losing friends, they remain loyal to gang culture.

As a consequence of drug use gang members are also universally poor. I’ve never seen a gang member living in luxury. Their homes are filthy. They wear clean clothes, but that’s about it. Generally they are lazy and don’t like to work. One gang informant missed a DMV appointment and a job interview because he was either “asleep” or “taking a shower.” That level of laziness is costly—not just to the gang member but to society at large. Gang culture is a lifestyle.

When Rules Replace Morality in Gang Culture

What’s most striking about gang culture is how rules replace personal ethics. Right and wrong become irrelevant. It’s about what the gang allows. Stealing from a civilian is okay, but stealing from a brother? Forbidden. Talking behind someone’s back can be more dangerous than carrying a weapon. To learn more read the blog Roles in Gangs: How Power and Profit Shape Street Culture.

Meetings are held not to foster community, but to assign hits, deliver beatings, or resolve business. The phrase “you do it or we do you” isn’t metaphorical. Orders from the top come with consequences. Associates often act as lookouts during these prison meetings, blocking or distracting guards if needed. One associate told me some members would attend meetings on a “need to know basis”. The phrase “need to know” reminded me of classified FBI operations/investigations—only this was for crime.

The Cost of Gang Culture

Gang culture may offer identity, but it comes at an immense cost. The structure mimics military discipline but enforces it through violence. The community it creates is conditional—one mistake and you’re shunned, beaten, or dead. Loyalty is demanded, not earned.

The numbers tell a sobering story. With 676 documented members, the Oxnard Colonia Chiques gang represents the largest criminal organization in Ventura County. The economic impact is staggering. In 2019, I analyzed the 676 gang member’s criminal histories which totaled 12,785 arrests. A low estimated cost of an arrest is $1,000. Members of the Colonia Chiques gang were arrested 12,785 times which cost $12,785,000, a burden primarily paid by the city of Oxnard and surrounding communities. To learn more read the blog Oxnard Colonia Chiques.

The Ventura County gang members I encountered are lost in a system they both depend on and are destroyed by. They crave belonging, but pay heavily for it. Gang members desperately want respect, but reject responsibility and avoid honest work. They follow rules, but the rules don’t protect—they enslave.

And yet, gang culture persists. As long as bad decisions and broken families exist, so will gangs. But understanding this culture—the rules, the rituals, the reasoning—offers a critical insight into how and why these groups continue to thrive. To learn more read the blog What to Do About Gangs A Street-Level Perspective.

I believe the solution lies in exposing gang culture‘s internal contradictions. Members seek respect but engage in self-destructive behavior. They want to belong but live by rules that destroy relationships. They desire identity but surrender individuality to group conformity.

To learn more about gang culture, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.