FBI Gangs: The Bureaucratic Reality Behind Federal Gang Enforcement

August 13, 2025

The public believes the FBI represents the pinnacle of American law enforcement. When it comes to dismantling criminal organizations, citizens expect federal agents to succeed where local police cannot. This perception creates dangerous misconceptions about FBI gangs operations and the federal government’s actual capacity to address street violence.

I spent years working FBI gangs cases. What I discovered contradicts everything the Bureau wants you to believe about federal gang enforcement. The reality is stark: bureaucratic obstacles, prosecutorial failures, and misplaced priorities consistently undermine effective gang investigations. If communities expect the federal government to solve their gang problems, they’re setting themselves up for disappointment. Let’s take a deeper look at the reality of FBI gangs and the bureaucracy that governs them.

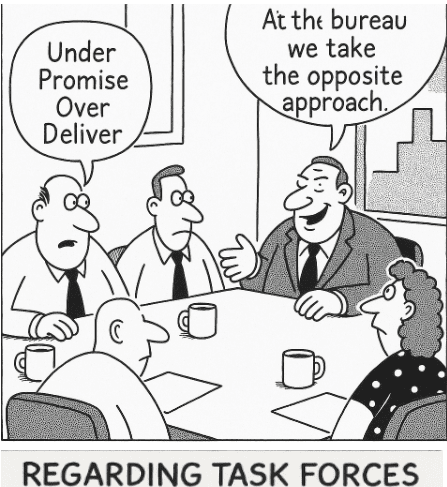

FBI Safe Streets Task Forces

Started in 1992, the FBI’s Safe Streets Task Forces (SSTFs) were established to combat violent crime—particularly gang- and drug-related offenses—through multi-agency collaboration. The goal is to disrupt and dismantle violent street gangs, drug trafficking organizations, and criminal enterprises by combining federal investigative capabilities with the localized knowledge of state and local law enforcement.

Each Safe Streets Task Force is a partnership between the FBI and local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. As of 2024, there are over 178 SSTFs operating in major cities and regions across the United States.

Safe Streets Task Forces are great in theory however, they are only as effective as the cooperation among the local, state, and federal agencies and the strength of their leadership. There are three critical issues that consistently undermine their success:

- Personnel quality

- Information sharing

- Leadership dysfunction

While most detectives and agents assigned to SSTFs are competent and hardworking, some organizations treat task forces as a dumping ground for lazy employees who can’t cut it in their home agencies.

Agencies eagerly participate in information sharing until it could result in divulging their own ongoing investigations, at which point cooperation evaporates and territorial instincts take over.

The FBI’s leadership approach proves particularly disastrous—I’ve witnessed FBI supervisors dictate investigative priorities to seasoned state and local officers instead of listening to their street-level expertise and community concerns. This heavy-handed federal approach destroys the trust and collaboration that SSTFs desperately need to function effectively, turning what should be cooperative partnerships into bureaucratic power struggles.

The Management Problem That Plagues FBI Gangs

The FBI’s organizational structure actively works against successful gang enforcement. Multiple layers of management—Supervisors, Assistant Special Agents in Charge, and Special Agents in Charge —create bottlenecks that slow decision-making to a crawl. When you’re trying to track fast-moving gang members who operate in real-time, bureaucratic delays prove fatal to investigations.

I watched FBI gangs cases collapse because FBI managers demanded endless approvals for basic investigative techniques. These supervisors, many of whom had never worked street-level gang cases. Bureaucracy rules over common sense. FBI management delayed signing operational plans while gang members continued trafficking drugs and committing violent crimes.

The disconnect between management expectations and investigative needs creates an environment where agents succeed despite leadership, not because of it. One veteran agent told me the secret to FBI work: “Accept that no one cares.” This cynical wisdom reflects the reality that FBI gangs agents face daily—indifference from above and active obstruction from bureaucrats who prioritize risk aversion over results.

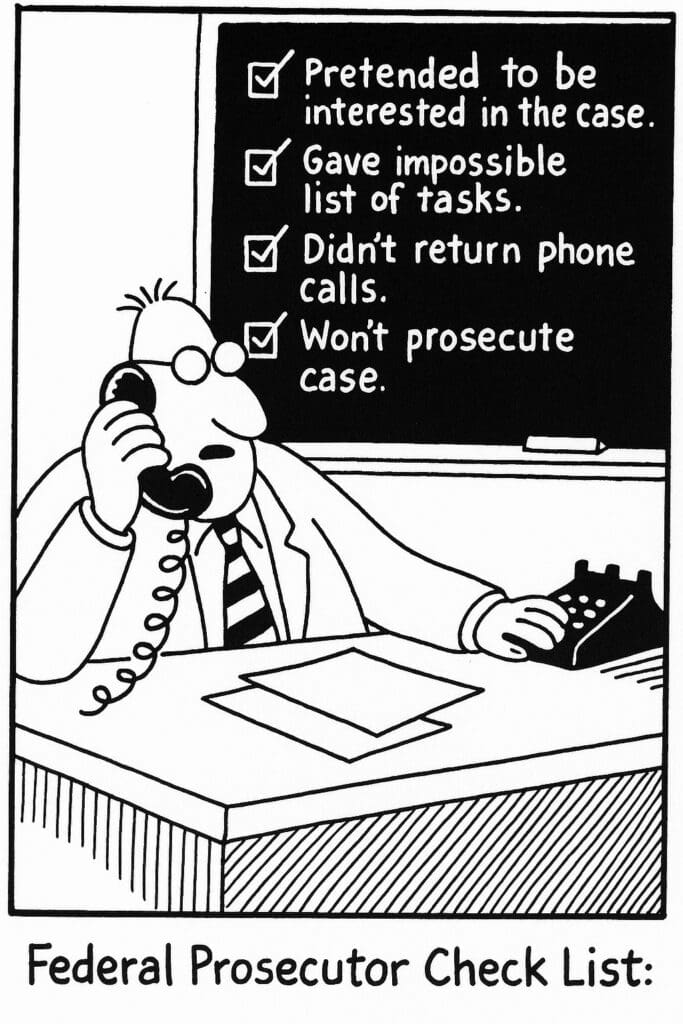

The Federal Prosecutor Problem in FBI Gang Cases

Even when FBI gangs agents build solid cases, they face another obstacle: reluctant federal prosecutors. The ivy league educated Assistant United States Attorneys often avoid gang cases due to their political sensitivity. I’ve met with prosecutors who say, “I understand the crime but these gang members are just poor people”. They create endless “to-do” lists, delay decisions, and reject cases for reasons unrelated to evidence quality.

Gang cases require prosecutors to work with imperfect witnesses—often former gang members or current drug users. Many Assistant United States Attorneys lack the stomach for this messy reality of street-level law enforcement.

On more than one occasion I’ve witnessed federal prosecutors promise prosecution to a room of local detectives only later to pretend to be too busy to prosecute the case.

The result is predictable: career criminals remain free while agents waste months building cases that prosecutors won’t file. This prosecutorial reluctance creates a feedback loop that demoralizes agents and local detectives. To learn more read the blog Laws on Gangs: What Works and What Doesn’t.

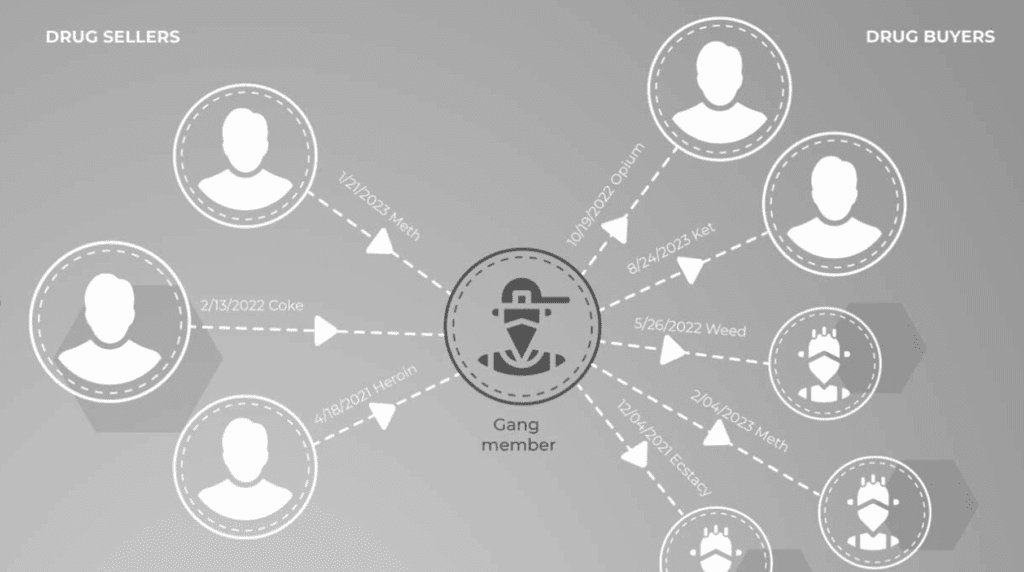

Intelligence-Based Approaches to FBI Gangs

Despite these systemic problems, effective FBI gangs enforcement is possible when agents focus on smaller prosecutable cases. There is a saying in the FBI; big cases big problems, small cases small problems, no cases no problems.

Gang investigators should focus on intelligence gathering rather than grandiose federal strategies. I developed detailed charts showing gang hierarchies, identifying who was incarcerated, felons, or facing immigration issues. Without this intelligence foundation, agents/detectives are essentially guessing. To learn more read the blog Roles in Gangs: How Power and Profit Shape Street Culture.

Social media provides unprecedented insight into gang structures and activities. Unlike traditional organized crime groups that want to be anonymous, gang members crave attention and document their activities online. They post photos displaying weapons, flash gang signs, and discuss criminal activities. This digital evidence proves invaluable in FBI gangs cases, but requires time-consuming search warrant processes that many investigators avoid. To learn more read the blog What to Do About Gangs: A Street Level-Perspective.

What Actually Works in FBI Gangs Operations

Based on operational experience, certain approaches consistently produce results in FBI gangs cases. Federal adoption of felon-in-possession firearm cases provides significant sentencing enhancements that remove violent gang members from communities for years instead of months.

Local wiretap orders and ping requests work faster than federal alternatives, which often get bogged down in approval processes.

Developing confidential human sources through partnerships with local detectives.

Social media search warrants, despite their complexity, provide crucial evidence for establishing gang membership among individuals without extensive criminal records. These digital investigations often reveal unknown gang members that would otherwise remain hidden.

Suppression Requires Speed and Coordination

The suppression phase of FBI gangs investigations includes:

- Arresting gang members with active warrants.

- Federally adopting firearm cases.

- Working with parole, probation, and local detectives to develop sources.

- Using local wiretaps.

- Seeking gang injunctions and civil enforcement actions.

Speed matters. The longer a gang member is free, the more damage they can do. Federal cases offer longer sentences, but only if prosecutors are willing to file them. That’s never a given.

The Myth of Gang Dismantlement

The FBI loves claiming it “dismantled” gangs, but this rhetoric rarely reflects operational reality. The flaw with dismantlement is the notion that sending gang members to prison will end their enterprise. When gang members go to prison they learn and are incentivized from the prison gang the Mexican Mafia/EME. Unfortunately, in prison gang members often make new drug contacts. To learn more read the blog La Eme.

Targeted suppression proves more realistic and effective than dismantlement claims. This approach focuses on continuous pressure, disrupting drug and weapon trafficking, and degrading operational capabilities rather than falsely claiming total victory.

FBI gangs operations should emphasize measurable impacts: reduced violent crime rates, successful prosecutions, and community safety improvements. Grandiose dismantlement claims create unrealistic expectations and divert resources from smaller suppression strategies. Ask yourself, “How many times has the FBI dismantled the Italian mafia?” Despite the “dismantlement” the mafia continues to exist.

Conclusion: Realistic Expectations for FBI Gangs Enforcement

The federal government will not solve America’s gang problem. Expecting the FBI to eliminate street gangs through bureaucratic processes designed for organized crime cases sets communities up for failure. The Bureau’s organizational culture and prosecutorial challenges create systemic obstacles that individual agents cannot overcome.

However, targeted FBI gangs operations can achieve meaningful results when agents focus on smaller cases that are intelligence-driven with the goal of suppression rather than dismantlement fantasies. Safe Streets Task Forces are a great starting point. Success requires partnerships with local agencies, realistic goal-setting, competent leadership, and persistent effort despite bureaucratic obstacles.

Communities seeking solutions to gang violence should invest in local law enforcement capabilities while using federal resources for supplemental assistance. The most effective FBI gangs operations support local efforts rather than replacing them.

Working FBI gangs cases demands persistence. There’s a quote I kept on my desk from President Calvin Coolidge: “Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.” The persistence required for successful gang enforcement comes not from fighting gangs themselves, but from navigating federal bureaucracy that often works against investigative success. Understanding this reality helps set appropriate expectations for what FBI gangs operations can realistically achieve.

To learn more about gangs, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.