The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime

September 12, 2025

Gang culture has never been static. From my 22 years as an FBI Special Agent investigating street crews in Los Angeles, Ventura County, and beyond, I saw firsthand how graffiti crews transformed into highly structured criminal organizations. What started as a spray-painted name on a wall morphed into violent enterprises dealing in narcotics, weapons, and murder. That transformation—the story of The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime—is one of the most important lessons for anyone trying to understand modern gang dynamics.

From Graffiti Crews to Criminal Identity

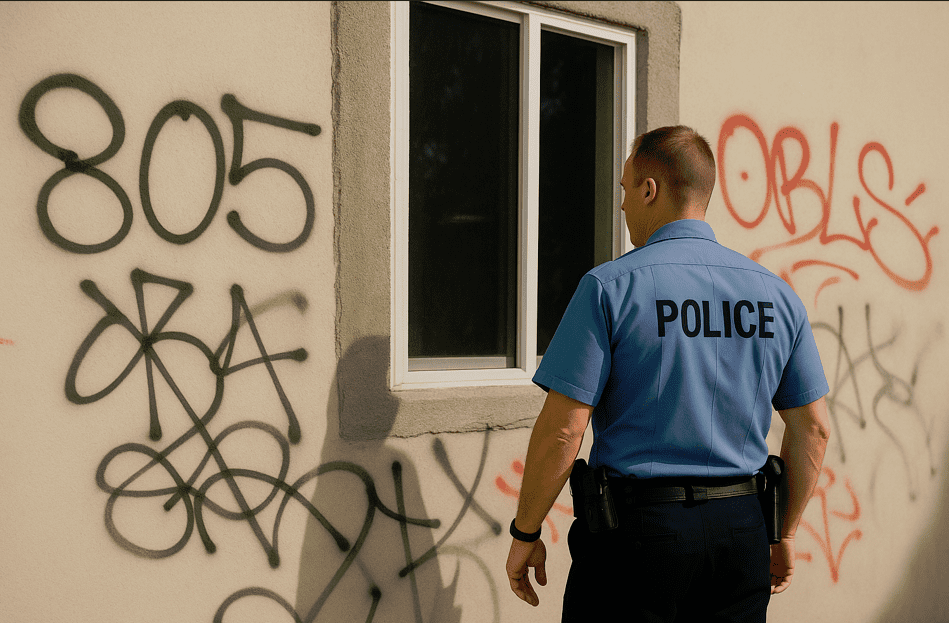

In the early stages, many groups began as neighborhood tagging crews. Their mission was to gain recognition by covering walls, bridges, and alleyways with their monikers. Graffiti was not just vandalism; it was an early form of branding. When young men sprayed their name across a city block, they were announcing territory, ego, and loyalty. But as my book Less Tagging More Killing explains, tagging quickly escalated into violence. To learn more read the blog Gangs and Violence: A Hidden Epidemic.

As rival crews crossed each other’s names out, disrespect turned into fistfights, then stabbings, and eventually shootings. The graffiti battles provided a training ground where loyalty was tested, and reputation became tied to violence. This shift marked The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime, where symbolic art became a precursor to territorial warfare.

Family Breakdown and Recruitment

Another driving force in The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime was environment. In cities like Oxnard and Santa Paula, I saw neighborhoods where fatherless households left young men vulnerable to recruitment. When legitimate pathways to success seemed difficult, gangs offered belonging, identity, and protection.

At first, that income was small—petty theft, burglaries, and low-level drug sales. But once the gangs realized their power extended beyond tagging walls, they expanded into organized rackets. It was never just about painting the block anymore; it was about owning the block.

Guns Replace Graffiti

The clearest turning point in The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime came with the widespread use of firearms. In the 1980s and 1990s, guns became the ultimate equalizer. A crew with access to firearms could dominate rivals and intimidate entire communities.

Graffiti still marked territory, but it was backed up by the barrel of a gun. In my investigations, I often found “hood guns”—shared weapons passed from one member to another. These guns were used in shootings, then hidden or discarded, making them nearly impossible to trace. Guns transformed tagging crews into feared criminal enterprises, and violence became their primary language. To learn more read the blog Guns and Gangs: A Deadly Combination.

The Influence of Prison Gangs

Street-level crews did not evolve in isolation. Prison gangs, particularly the Mexican Mafia (La EME), played a decisive role in shaping The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime. Local cliques that once painted walls found themselves paying “taxes” to prison shot-callers in exchange for protection. No organization has done more damage to the Mexican American community in California than the Mexican Mafia. To learn more read the blog La Eme: Mexican Mafia Control Over California Gangs.

Once prison gangs asserted authority, the neighborhood crews adopted stricter hierarchies. Drug money was sent upstate to the prison gang the Mexican Mafia. Rules were enforced with beatings or executions. Gangs that had once fought over graffiti learned to cooperate under prison orders, especially in narcotics trafficking. I witnessed Ventura County street gangs align themselves with larger organizations, proving that tagging had fully given way to organized criminal structures.

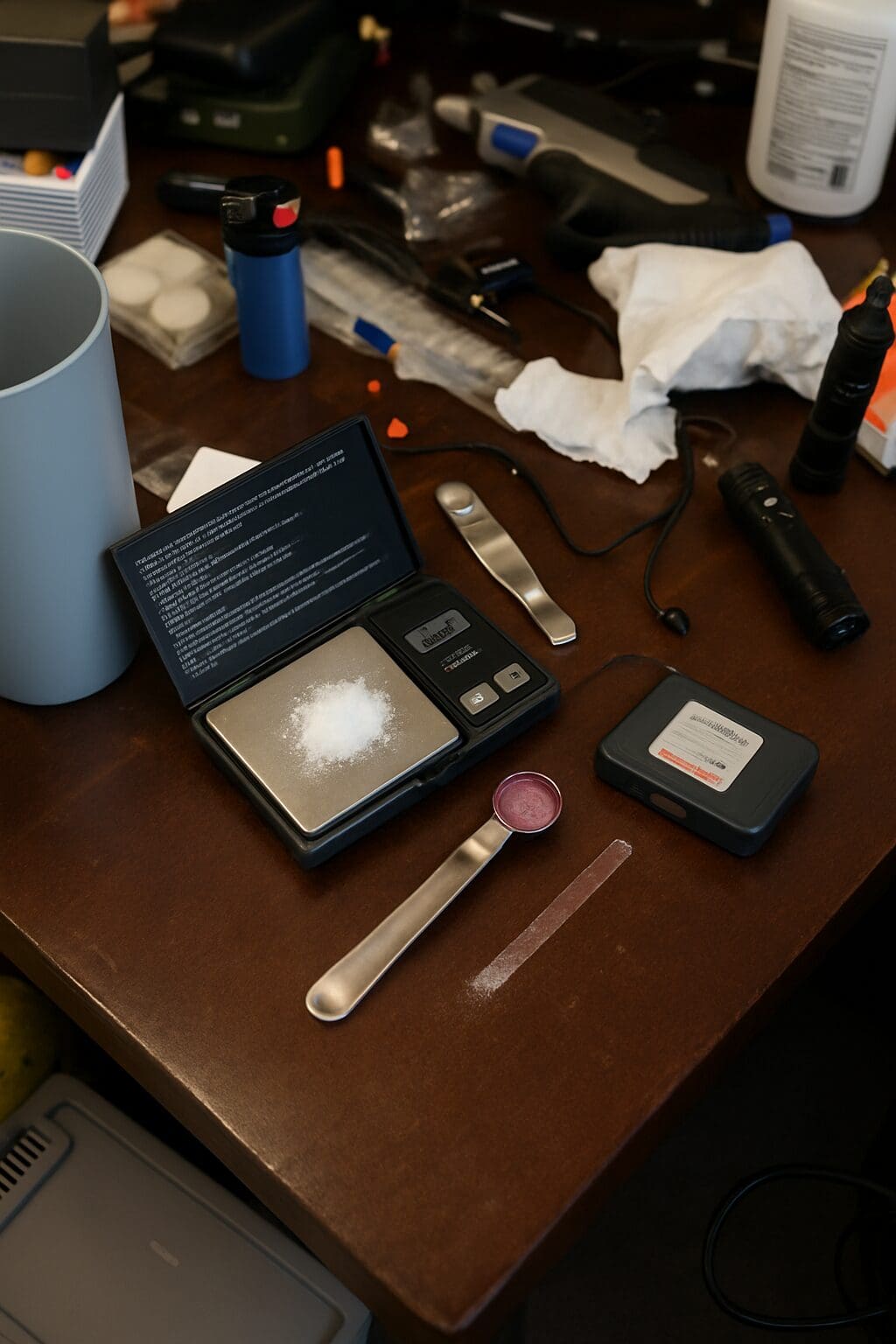

Drug Trafficking and Extortion

With organization came profit. Drug sales became the lifeblood of gangs across Southern California. In Oxnard, Santa Paula, and Ventura, crews shifted from tagging buildings to controlling neighborhoods where methamphetamine, heroin, and later fentanyl were sold.

Extortion soon followed. Drug dealers were forced to pay “rent” or “taxes” to operate in gang-controlled neighborhoods. What had started as graffiti crews now resembled traditional organized crime families, enforcing rules with violence and extracting income through intimidation.

This stage solidified The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime—money, rather than graffiti, became the primary motivator. Young men join the gang for belonging but older members see youth as a means to make money. To learn more read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Law Enforcement Response

From the law enforcement perspective, understanding The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime was critical to developing strategies. Early efforts focused on graffiti abatement programs—painting over tags to discourage territorial claims.

We shifted toward federal prosecution of firearm and drug offenses. Law enforcement recognized gangs as organized crime syndicates, or as we described them in the Bureau “criminal enterprises”. To learn more read the blog What to Do About Gangs: A Street-Level Perspective.

Community Impact

What started in the late 1970’s in Santa Paula with twelve gang members has ballooned to over 200. Same with the city of Oxnard, the gang was located on the other side of the tracks in the Colonia neighborhood, and now gangs are all over the city. Failures by city leaders to address the gang problem has only allowed it to grow. To learn more read the blogs Santa Paula Gangs: Mayberry Gone Wrong, Oxnard Colonia Chiques: History and Violence.

The social costs of The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime are devastating. Neighborhoods once plagued by graffiti now live under the shadow of shootings, drug overdoses, and extortion. Families who once complained about vandalized fences now fear stray bullets. Children raised in these environments face daily pressure to join or at least align with local gangs.

In Ventura County, I calculated millions of dollars are spent annually on arrests, probation, and incarceration tied to local gangs. Beyond the numbers, the emotional toll—broken families, lost lives, and traumatized communities—is immeasurable. To learn more read the blog Top 10 Most Dangerous Gangs in Ventura County.

Technology and the New Era

Today, The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime continues with a digital twist. Social media platforms now replace walls as places for gang members to flex their identity. Instead of tagging alleys, members post videos flashing guns, cash, and colors. Disrespect happens in the comments section, and retaliation can occur within hours.

Lessons Learned

Looking back on decades of investigations, I can say with certainty that The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime teaches several lessons:

- Symbols always escalate – graffiti may start as expression, but it inevitably transforms into territorial violence.

- Environment matters – family dysfunction and politicians deny that there is a problem.

- Prison gangs organize the streets – the influence of incarcerated leaders cements criminal hierarchies.

- Money trumps pride – once gangs realize profit potential, criminal enterprises replaces tagging.

Conclusion

The journey from tagging walls to running organized crime rackets is not just the story of graffiti gone wrong—it is the story of modern gang culture. My book Less Tagging More Killing documents this transformation with case files, firsthand interviews, and courtroom battles.

The phrase “The Evolution of Gang Violence: From Tagging to Organized Crime” is more than a blog title; it’s the reality I witnessed for decades. Communities that once dismissed tagging as a nuisance found themselves living in neighborhoods dominated by drug dealers and killers.

Understanding this evolution is essential if society hopes to respond effectively. Erasing graffiti is not enough. We must recognize the forces that transform a spray can into a pistol, a tagging crew into a cartel, and a neighborhood problem into a national crisis.

To learn more about gangs get the book Less Tagging More Killing.