Gangs and Hood Guns: A Hidden Arsenal on the Streets

September 27, 2025

This blog explores the reality of gangs and hood guns, drawing from case examples, police records, social media exchanges, and federal prosecution strategies. It also examines how local and federal law enforcement agencies struggle to combat the problem.

When talking about gangs, few images are more telling than gang members sharing a single weapon among themselves—a community firearm used to protect territory, commit crimes, and intimidate rivals. These shared firearms, often called “hood guns,” play a central role in gang life and criminal culture. The gang’s practice of passing hood guns from one member to another is not just a practical response to limited resources; it is a calculated tactic designed to avoid law enforcement detection, increase group loyalty, and maintain a climate of fear. To learn more read the blog Gangs and Violence: A Hidden Epidemic.

What Are Hood Guns?

The term “hood gun” refers to a firearm that is shared among multiple gang members. Unlike legally owned weapons, these guns are almost always stolen, bought on the street, or smuggled into the community. Because most gang members are already convicted felons or on probation or parole, owning a firearm individually carries significant legal risks. Sharing the weapon provides plausible deniability and dilutes responsibility.

In Ventura County, both the 12th Street Locos and Northside Chiques exemplify the practice. Police routinely encountered vehicles with multiple documented gang members, only to find a pistol hidden under a seat or stashed near a seatbelt. When questioned, members often negotiated among themselves about who would “take the rap” for the firearm. This cooperative dishonesty demonstrates how gangs and hood guns operate as a collective defense system against law enforcement. In one case a Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) test of a firearm found under a car seat linked all three Northside Chiques gang members had handled the weapon.

To learn about Oxnard and Santa Paula gangs read the blogs: Oxnard Colonia Chiques, Santa Paula Gangs: Mayberry Gone Wrong.

Firearms as Tools of Status and Fear

In the culture of gangs, firearms serve more than a defensive role. They are symbols of power and intimidation. A gang member in possession of a hood gun enhances both his individual status and the reputation of the gang. The weapon becomes a mobile badge of honor, shared and circulated to project dominance in the community. Hood guns often have the gang’s name scratched on the handle.

Drive-by shootings remain one of the most notorious uses of gangs and hood guns. These attacks, often retaliatory, rely on access to firearms that can be quickly passed to whoever is tasked with carrying out the violent mission. Even when not used, the mere rumor that a gang has guns available enhances its ability to instill fear in rivals and local residents. To learn more read the blog about Guns and Gangs: A Deadly Combination.

The Code Words for Guns

Like every subculture, gangs develop their own slang to refer to weapons. Firearms are rarely called by their legal names; instead, terms such as “strap,” “toy,” “thang,” or “heat” are used. Social media exchanges captured between gang members reveal how embedded this coded language has become.

For example:

- “Some caca boy pulled a toy on me” meant a rival pulled a gun.

- “Don’t get kaught slipping without it” reminded members never to be caught unarmed.

- “$140 for this shoti, hmu” was an offer to sell a sawed-off shotgun.

These casual digital conversations show how the market for gangs and hood guns functions in plain sight, often cloaked only by a thin veil of slang.

Beginning in the early 2000’s the Do it Yourself (DIY) business model for firearms enthusiasts gradually grew and become widely available. Around 2013–2014, companies began selling “80% lower” receivers and complete build kits online to the general public. These untraceable weapons (ghost guns), lacking serial numbers and sold as DIY kits. To learn about ghost guns read the blog Gangs and Ghost Guns: The Deadly Intersection of the Loma Flats Gang and Law Enforcement.

Losing a Hood Gun

While guns are a precious commodity in gang culture, they are sometimes lost, stolen, or confiscated. Conversations between gang members reveal how seriously such losses are taken. One member might be mocked for “not being laced up” (not being smart or careful enough) after losing a weapon. Others lament the financial value of the lost gun, calling it “long feria” (worth a lot of money).

This dynamic underscores the dual nature of gangs and hood guns: they are both emotional symbols of protection and cold economic assets.

Guns and the Drug Trade

Firearms are indispensable tools for gangs involved in narcotics sales. Street-level dealers face constant risks of robbery from rivals or opportunistic criminals. Possessing a hood gun deters these threats and demonstrates to buyers and competitors alike that the dealer is protected. To learn more read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

In Ventura County, gang members openly admitted that handguns purchased for $500 in the U.S. could be smuggled and resold in Mexico for double the price. This cross-border gun trade shows how gangs and hood guns are not confined to neighborhood turf wars; they are part of a broader economic system that fuels both domestic and international criminal networks.

Law Enforcement Challenges

Despite frequent arrests of armed gang members, successfully prosecuting these cases is complicated. One challenge is ownership—when multiple people ride in the same car with a firearm hidden under a seat, pinning responsibility on a single defendant is difficult. Forensic tests such as fingerprint analysis and DNA examinations can help determine who possessed the weapon.

Body-worn cameras became game-changers, capturing suspects discarding guns and making incriminating statements on video. These recordings stripped defense attorneys of their ability to exploit inconsistencies in police reports. To learn more read the blog Laws on Gangs: What Works and What Doesn’t.

Federal Laws and Prosecution Strategies

The most effective charge against armed gang members has been 18 U.S.C. 922: Felon in Possession of a Firearm. This federal statute allows prosecutors to bring straightforward, easily provable cases against repeat offenders. New Assistant U.S. Attorneys often used these cases to gain courtroom experience, making them an ideal entry-level prosecution tool.

In Ventura County alone, dozens of gang members were federally prosecuted under this statute. The presence of gangs and hood guns meant that almost any arrest of a felon with a firearm could be elevated to a federal case. Once indicted, the suspect typically faced four years in prison, removing dangerous individuals from the streets.

Case Studies: Guns Hidden in Plain Sight

Several local cases illustrate the lengths gang members go to conceal firearms:

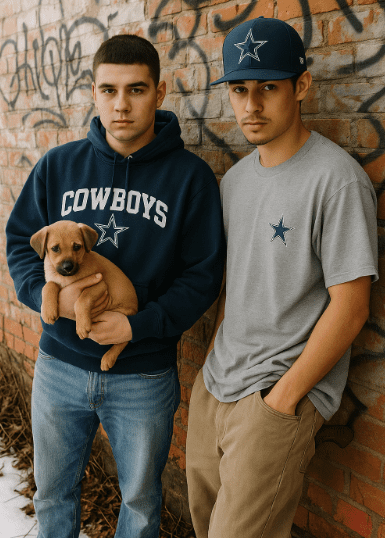

- The Puppy Decoy: During an Oxnard police search, a gang member clutched a puppy tightly to distract officers. Body-camera footage later revealed a loaded handgun hidden in his pocket.

- The Rifle Down the Pants: Another gang member, stared at his phone and repeated “I’m not doing nothing.” The gang member refused to stand when asked by police. Officers soon discovered he had a loaded .22 caliber rifle shoved down his pants, its stock carved with gang graffiti to mark it as a hood gun.

What were these two gang members hoping for? A confrontation. If a citizen or rival gang member spoke to them, they would, in gang slang, get “blasted.” These examples illustrate how deeply ingrained gangs and hood guns are in everyday street interactions. To learn more read the blog Inside Gang Culture: Rules and Rituals.

The Bigger Picture: Gangs, Guns, and Society

The persistence of gangs and hood guns flow into communities primarily through theft and straw purchases. A “straw” purchase of a gun is when one person (the straw buyer) legally buys a firearm on behalf of someone else who either can’t lawfully buy it themselves (for example, because they’re a prohibited person) or wants to hide their involvement. Demand remains high because gangs rely on firearms for protection, intimidation, and profit.

At the same time, lenient state laws like California’s Proposition 47—which reduced many drug and property felonies to misdemeanors—have changed the prosecution landscape. Gang members previously convicted of felonies were reduced to misdemeanors. Local cases that once could have been handled at the state level now often require federal involvement to achieve meaningful sentences.

Conclusion: Why Hood Guns Matter

Hood guns are more than just weapons; they are the heartbeat of gang violence. By being shared, hidden, and passed around, they represent the collective will of the gang to resist authority and project power. They fuel shootings, intimidate communities, and provide protection for the drug trade.

From social media slang to smuggling operations, the culture of gangs and hood guns is woven into the fabric of street life in places like Ventura County. Combating this issue requires cooperation between local police, federal agents, and prosecutors.

To learn more about gangs and hood guns, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.