Guns and Gangs: A Deadly Combination

June 11, 2025

For decades, the relationship between guns and gangs has been one of lethal efficiency. Firearms are more than just tools of violence; they are currency, status symbols, and instruments of power. Gang members refer to a gun as a ‘strap,’ ‘toy,’ ‘thang,’ or ‘heat’.

Take this typical social media exchange between two gang members:

Gang member 1: Some foo pulled a toy on me

Gang member 2: Ask me 4 a toy

Gang member 1: I thought I was going to get blasted…I need a strap

Gang member 2: $150 for this shoti, hmu (photo of sawed-off shotgun)

These aren’t kids talking about video games. This is the transactional language of guns and gangs—based on rage, retribution, and survival.

The Problem: State-Level Limitations

The revolving door of local justice frustrated me immensely. I watched as armed gang members cycled through county jails only to return to the streets within months. The state system, hampered by overcrowding and lenient sentencing guidelines, simply couldn’t contain the threat.

In one particularly absurd case, officers arrested a known gang member with a loaded firearm, a local judge sentenced him to 300 days in county jail, and he returned to his bicycle in the neighborhood three months later after receiving credit for “good time”. Three months! The message this sends about guns and gangs couldn’t be clearer: the consequences don’t match the crime.

California’s Proposition 47 compounded the problem. By reducing many felonies to misdemeanors, it inadvertently weakened our ability to keep dangerous individuals away from communities. Several felony convictions for gang members were reduced to misdemeanors. The practical effect was gang members who previously were prohibited from having a firearms due to a felony conviction, were now held minimally by the law for carrying a firearm.

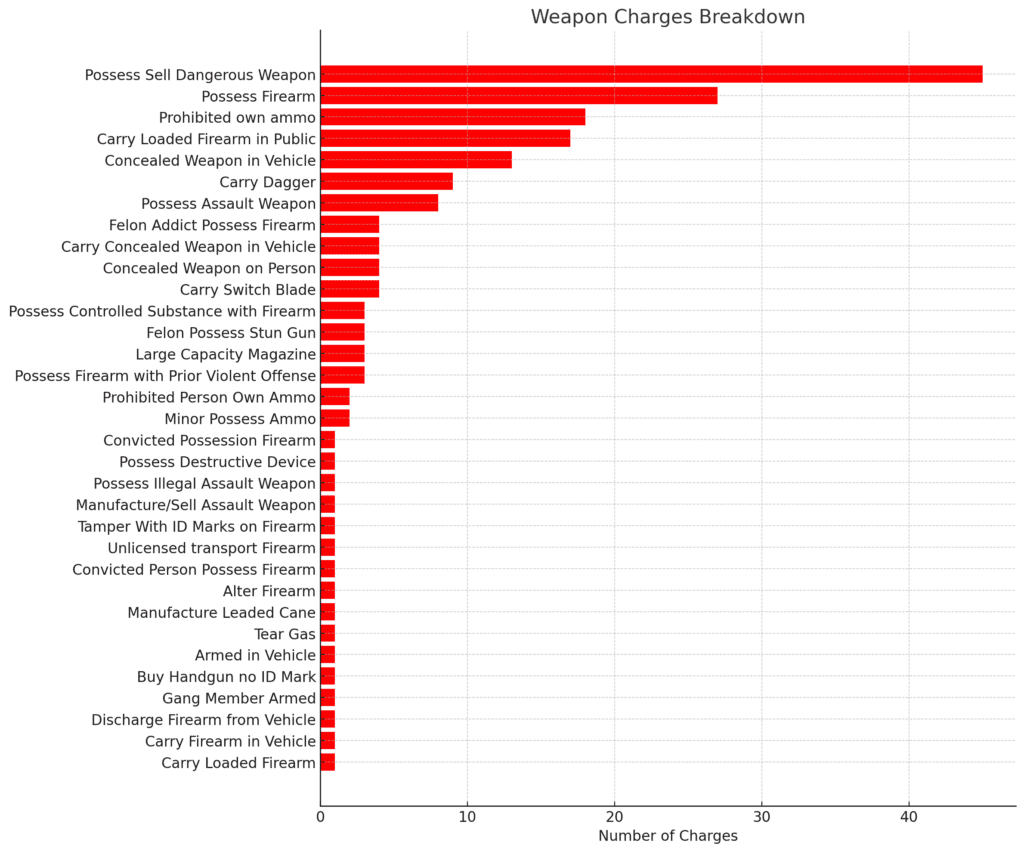

Guns and Gangs Charges with Weapons

I reviewed the criminal histories of the Santa Paula gang the Crimies. Above is a breakdown of the gang members charges for weapons offenses. PC 12020 Possess/Sell Dangerous Weapon 45 charges and PC 12021 Possess Firearm 27 charges accounted for 29% of the charges, in the weapons category. There is a federal law 18 U.S.C. 922 (Felon in Possession of a Firearm) which was used effectively against gang members with guns.

The Solution: Federal Prosecution

I learned quickly that prosecuting guns and gangs at the federal level was more effective than pursuing cases through local courts.

Federal prosecution offers distinct advantages when targeting guns and gangs. The combination of stronger sentencing guidelines, mandatory minimums, and no-bail policies creates a more effective deterrent.

My first step was meeting with a Supervisory Assistant U.S. Attorney. “What do you need to prosecute a felon in possession case?” I asked. The requirements were straightforward:

- Verification of a felony conviction

- Body camera footage

- Ideally a confession

- ATF certification proving interstate commerce

With this roadmap, I restructured my investigative approach. Every case needed to meet these specific criteria. The payoff was immediate and significant. Over my career, I participated in approximately 20 successful federal prosecutions of gang members who were charged for possessing firearms. The average sentence? Four years. Compare that to the three months in state custody from my earlier example. To learn more read the blog Laws on Gangs: What Works and What Doesn’t.

The Power of Body Cameras Guns and Gangs

Body-worn cameras transformed how we prosecute guns and gangs cases. Before this technology, defense attorneys could challenge officer testimony, creating reasonable doubt. With video evidence, these challenges collapsed.

I remember freezing a frame that showed a gang member literally throwing a sawed off shotgun mid-flight. The defense attorney’s face said everything. How do you argue with reality?

In another case, I brought a boxed firearm to a downtown Los Angeles office building after a federal public defender demanded to see the evidence. When I offered it, the senior federal public defender physically recoiled, confessing, “I’m afraid of guns.” I couldn’t help but notice the irony: she defended criminals whose lives revolved around guns and gangs, yet she was terrified of the very weapon at the center of the case.

Ghost Guns: Adapting to New Threats

The relationship between guns and gangs evolved as technology did. By 2019, we faced a new challenge: ghost guns, which are firearms that are put together by components purchased either as a kit or as separate pieces. These un-serialized, untraceable weapons flooded street markets, creating an enforcement nightmare. Without serial numbers, proving interstate commerce, or that the “firearms” traveled across state lines, became nearly impossible.

We adapted again. Using the ammunition provision in federal code (18 USC 922), we charged gang members with felon-in-possession of ammunition instead. If the bullets crossed state lines, the federal case remained viable. This creative solution allowed us to continue disrupting the guns and gangs pipeline despite technological evasion.

One such case resulted in a 15-year sentence after we caught a gang leader with both a ghost gun and substantial quantities of methamphetamine. The message was clear: innovation in crime would be met with innovation in prosecution. To learn more read the blog Gangs and Ghost Guns: The Deadly Intersection of the Loma Flats Gang and Law Enforcement.

Real Impacts on Community Safety

The effects of this approach rippled through gang territories. Local officers reported seeing fewer firearms on known gang members. The word had spread: federal charges meant serious time.

In Santa Paula, a community previously plagued by armed gang activity, officers noticed a marked decrease in visible firearms. The guns and gangs equation had changed—carrying weapons was no longer worth the risk. To learn more about gang violence see the blog Gangs and Violence: A Hidden Epidemic.

This wasn’t merely anecdotal. The data supported what we were seeing:

- Average federal sentence for guns and gangs cases: 4 years

- When drug charges were included: 7 years

- Longest sentence achieved: 15 years

- Plea rate: 100% due to body worn cameras

- Firearms removed from streets: 18 in my cases alone

Not one case went to trial. The evidence with body camera footage was simply too overwhelming.

Lessons Learned Guns and Gangs

My experience with guns and gangs cases taught me several valuable lessons:

- Local-federal partnerships are essential. When jurisdictions work together, enforcement becomes more effective.

- Technology matters. Body cameras aren’t just about accountability—they’re powerful evidentiary tools.

- Adaptability is crucial. As criminal tactics evolve to “ghost guns”, so must our responses (charge the ammunition).

- Consistent consequences create deterrence. When consequences are predictable and severe, behavior changes.

- Focus resources on the most dangerous offenders. Targeting those gang members who carry guns.

Conclusion Guns and Gangs

The fight against guns and gangs is not won with slogans. It’s won with cameras, convictions, and consistency. Every federal case that removed a violent gang member from the streets was a small victory for the community. A common goal was to take the criminals “out of the game” or off the streets and into custody.

Guns and gangs feed off each other—status, drugs, revenge, fear. But with the right strategy and persistence, law enforcement can break that cycle.

My experience investigating these cases convinced me that removing armed gang members from communities saves lives. No good ever came from a gang member carrying a firearm. It gives neighborhoods breathing room to heal and rebuilds public confidence in safety.

The relationship between guns and gangs represents one of our most persistent public safety challenges. But with strategic prosecution, technological advantages, and jurisdictional cooperation, we can disrupt this deadly partnership. One case, one firearm, one community at a time.

To learn more about guns and gangs, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.