Gang Initiation Fight: Understanding the Brutal Gateway to Gang Life

July 1, 2025

The gang initiation fight that begins a gang member’s life is more than a physical beating—it’s the culmination of a host of failures of parents, cultural dynamics, and individual despair.

I’ve investigated hundreds of gang members throughout my career in law enforcement. Each one started their criminal journey the same way: through a gang initiation fight. Calling it a fight is inaccurate, a better description is a beating. This brutal ritual isn’t just violence for violence’s sake. It’s the gateway that transforms confused teenagers into lifetime criminals.

In Ventura County alone, over 1,500 Mexican-American males have endured a gang initiation fight to join criminal street gangs. When I first reviewed gang rosters from Santa Paula, Thousand Oaks, and Oxnard, one fact struck me immediately. They all looked identical: young, male, Mexican-American. I asked: Why are so many Mexican-American males joining gangs? To learn more see the blog Why Do People Join Gangs?

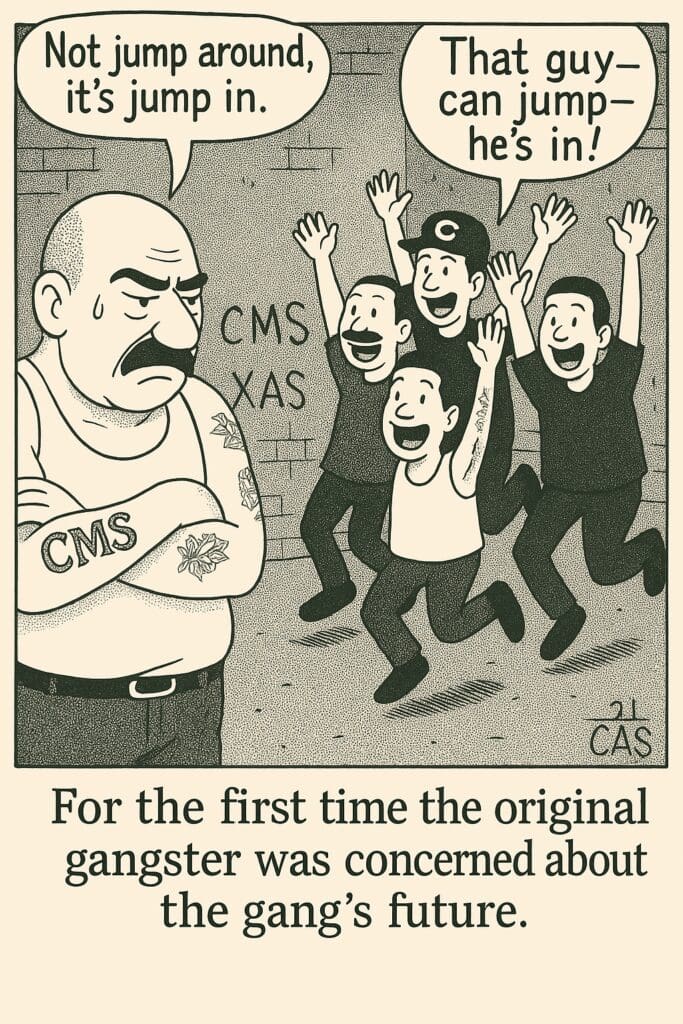

What Is a Gang Initiation Fight?

A gang initiation fight—commonly called being “jumped in”—follows a brutal but predictable pattern. The prospect faces multiple gang members in a coordinated beating. In Ventura County, this gang initiation fight typically lasts exactly 13 seconds. The number isn’t random. It represents allegiance to the prison gang EME (Mexican Mafia)—’M’ is the 13th letter of the alphabet. To learn more about the Mexican Mafia see the blog La Eme.

During this gang initiation fight/beating:

- The prospect is beaten by multiple gang members

- A senior member keeps precise time

- No weapons are used

- The beating stops exactly at 13 seconds

- The prospect becomes a full member immediately

I’ve interviewed dozens of gang members about their gang initiation fight experience. Most describe it as terrifying yet necessary. One told me: “I was scared, but I wanted it (to belong somewhere) so badly I was willing to do it.”

The True Purpose of Violence

The gang initiation fight serves multiple purposes beyond membership initiation. It creates psychological bonds through shared trauma. Fighting establishes hierarchy through violence tolerance. It eliminates weak prospects who might cooperate with law enforcement.

Most importantly, the gang initiation fight transforms normal teenagers into individuals capable of extreme violence. This isn’t accidental—it’s the entire point.

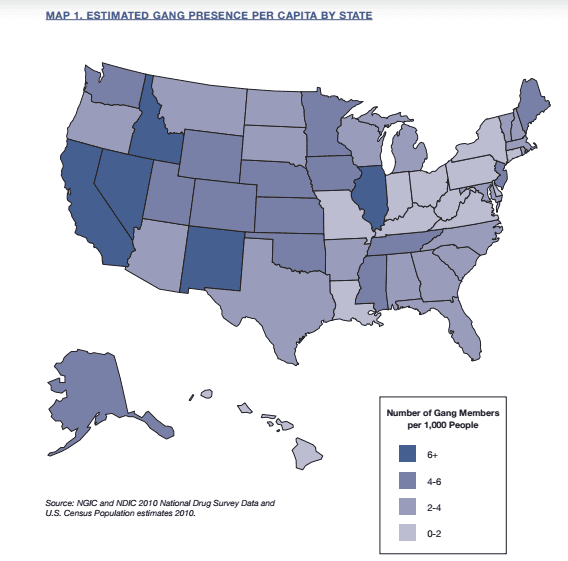

The Numbers Don’t Lie

Walter B. Miller’s seminal 1982 research found that while gang members made up only 6% of youth ages 10 to 19 in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, they were responsible for 11% of all arrests and 40% of serious crime arrests, including nearly a quarter of juvenile homicides.

My experience in Ventura County confirms this pattern: gang members here have longer and more violent criminal records than the organized criminals I investigated in Los Angeles. California has a higher ratio of gang members than 90% of the United States.

One gang member I tracked had 76 arrests. His crime spree began immediately after his gang initiation fight at age 15. The FBI’s 2011 National Gang Threat Assessment showed gang members commit roughly 48% of community crime. After reviewed gang members criminal histories, I suspect Ventura County’s numbers are higher.

Why Do They Choose the Fight?

Gang initiation fights represent much more than a test of toughness—they are rituals of acceptance for youth who often feel unwanted and disconnected. It’s a desperate search for belonging. I’ve identified two primary motivations:

First, Family Dysfunction: Most gang members I’ve interviewed share similar backgrounds.

Absent fathers—often working multiple jobs or incarcerated.

Overworked mothers—unable to supervise their children.

Neglect and abuse—many reported sad, abusive childhoods usually due to substance abuse. Gang membership acts as a surrogate family.

One gang member explained: “We weren’t supervised. Our parents were always working. We looked for something—and we found it in gangs.”

Second, Cultural Identity Crisis: The gang initiation fight becomes a twisted rite of passage. Hispanic gangs aren’t protecting their community from outside threats. They’re fighting other Mexican-American gangs in an endless cycle of self destructive violence.

The Initiation Process

I’ve observed how gangs recruit prospects for their gang initiation fight. The process typically begins in junior high school. No one is forced to join a gang. Many recruits are multi-generational—fathers and uncles introduce younger relatives to gang life. I’ve seen couples dress their newborn babies in gang clothing onesie.

Some gangs offer alternatives to the traditional gang initiation fight. Members can be “crimed in” by committing serious offenses. Female gang members are sometimes “sexed-in”, where sex with multiple gang members acts as the entry ticket. To learn more about female gang members see the blog Gang Initiation for Females: The Untold Reality Behind the Drama. Others allow relatives to bypass the beating entirely. However, these members face constant disrespect from those who endured the full gang initiation fight.

The Role of Poverty, Family, and Culture

In Santa Paula, 22% of children live below the poverty line, and 20% of families are single-parent households. The population is about 80% Hispanic, with a strong Christian cultural identity that largely opposes abortion.

Freakonomics authors Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner proposed that childhood poverty and single-parent homes strongly predict criminal behavior. This resonates with what I’ve seen: unwanted children often end up in gangs. The religious opposition to abortion within Hispanic communities means more unwanted children are born into conditions ripe for gang recruitment. To learn more read the blog Hispanic Gangs: Inside the Dirty Nickel.

EME Perpetuates the Cycle

The gang initiation fight is just the beginning. Most gang members eventually are incarcerated. In Ventura County Jail, they maintain their street gang identity. But state prison changes everything.

In California’s prison system, all Southern California Hispanic gang members (south of San Jose) become Surenos. The same young men who fought bloody turf wars must now work together under the prison gang EME’s authority. Their street gang rivalries become irrelevant.

Prison hierarchy operates through violence and intimidation. EME controls the Sureno population with strict codes:

- Physical training requirements

- Absolute respect for ranking members

- Escalating punishment system

No group has done more damage to Mexican/American males than the prison gang Eme or the Mexican Mafia.

The Cost of Belonging

EME’s punishment system reveals the true cost of gang membership.

Eme associates and members punishments escalate:

- First offense: beating

- Second offense: shunning—deeply painful for those who crave belonging

- Third offense: death

One EME associate explained: “Being shunned was worse than any beating. You’re completely alone—and nobody wants to be alone in prison.”

This desperation for belonging drives the entire cycle. The gang initiation fight promises acceptance but delivers only deeper isolation and violence.

The Unspoken Tolerance of Gangs

I’ve noticed a disturbing parallel between gang tolerance and other social issues. Years ago in Germany, local mayors begged the U.S. Army not to close military bases. Young American soldiers caused significant problems, public drunkenness, assaults, rape, but they also brought money. Economic benefit trumped criminal behavior.

Ventura County operates similarly. The agricultural industry depends on Hispanic labor worth billions annually. Local leaders seem content letting gang violence remain internal—as long as it doesn’t spread beyond certain neighborhoods.

Ventura County gang members fight other Mexican-American gangs, not white, Asian, or Black groups. Many local officials turn a blind eye to this contained violence.

Breaking the Cycle

I’ve spent years studying gang dynamics and identified several solution points:

Family Intervention: Strong family structures prevent gang recruitment. Regardless of how poor a family my be if the children have loving parents the likelihood of gang membership decreases.

Cultural Shift: Hispanic communities must acknowledge that gang culture destroys their own children. The gang initiation fight isn’t a rite of passage—it’s a sentence of an unfulfilled life. Parents who promote the gang lifestyle should be charged with child abuse.

Final Assessment

I often reflect on this: Why does society tolerate this cycle?

Just as Burgermeisters (mayors) in Germany tolerated drunk violent soldiers because of economic benefit, many American communities tacitly tolerate gang violence—as long as it stays in certain neighborhoods.

Every gang initiation fight represents multiple system failures:

- Failed parents unable to provide guidance

- Failed communities tolerating violence

If we want fewer gang initiation fights, fewer beatings, and fewer funerals, we must address the root causes, not just the symptoms. We need comprehensive intervention addressing family dysfunction.

Until we address these root causes, another confused teenager will step into that circle, hear “time starts now,” and get beaten to prove he belongs somewhere—anywhere.

To learn more about gang initiation fight, get the book Less Tagging More Killing: