Laws on Gangs: What Works and What Doesn’t

July 16, 2025

Lawmakers created laws on gangs to help communities fight back against violent crime, but too often those laws fall short when authorities apply them inconsistently or lack the will to enforce them. As someone who spent years investigating gangs across Southern California, I’ve seen firsthand what works—and which laws simply don’t. Understanding the difference can make or break suppressing a gang.

I agreed with the findings of the National Institute of Justice, which determined that the most effective gang suppression strategy was to leverage weapons and narcotics enforcement to federally prosecute violent gang members. The result? Longer sentences and greater disruption to criminal enterprises. These conclusions are not abstract—they mirror what I experienced while working with state and local law enforcement and the FBI.

In 2014, federal prosecutors successfully brought drug convictions against multiple gang members in Oxnard, California, aided by two dedicated Oxnard Police Department (OPD) detectives embedded in an FBI task force. The outcomes were commendable, but even with numerous arrests and lengthy federal sentences, violence in Oxnard did not decline. Eventually, OPD pulled their detectives back due to staffing issues, cutting short what was proving to be a promising collaboration. Despite the wins in court, the price of methamphetamine dropped—proof that prosecuting gang members alone doesn’t necessarily impact drug supply chains or street-level violence.

In spite of having comprehensive laws on gangs on the books, several approaches consistently failed to deliver expected results. To illustrate lets look at laws that suppress gangs.

Two Federal Laws That Worked in Suppressing Gangs

Gun Law

Congress passed the Gun Control Act of 1968. The goal of the law was to restrict interstate commerce in firearms and prohibit possession by certain categories of people (e.g., felons, fugitives, drug users, etc.)

When police catch a person previously convicted of a felony with a firearm, that person violates both federal and state law. Federal prosecution under 18 USC 922 (felon in possession of a firearm), was highly effective. I adopted roughly 20 of these cases involving gang members, all of which ended in guilty pleas. The average sentence was four years—far longer than anything imposed by state courts. Some of the enhancements that lengthened sentences included having multiple guns, obliterated serial numbers, or extended magazines. If the weapon is a “ghost gun” technically it is not a firearm, instead charge the ammunition which is part of the statute.

Felon-in-possession gun cases allowed us to remove dangerous individuals efficiently and was one of the ideal laws on gangs. Federal court doesn’t use bond. If police arrested the gang member with a gun, the judge deemed him a danger to the community and remanded him. To learn more see the blog Guns and Gangs: A Deadly Combination.

Drug Law

Congress passed Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. Federal prosecution under 21 U.S.C. 841(a) prohibits knowing or intentional manufacture, distribution, dispensation, or possession with intent to manufacture, distribute or dispense a controlled substance. This statute is one of the most frequently used laws in federal drug prosecutions and forms the basis for most federal narcotics trafficking charges.

From an investigative standpoint, methamphetamine cases are ideal. Specifically, the drug is cheap to buy but carries severe federal penalties. Five grams of pure meth can trigger a five-year mandatory minimum sentence. Fifty grams can get a defendant ten-year mandatory minimum sentence. To learn more see the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Gang Injunctions Work

In March 2004, the Ventura County District Attorney’s Office and the City of Oxnard enacted a gang injunction that targeted the largest and most entrenched gang in Oxnard, Colonia Chiques.

Specifically, the purpose of the gang injunction named 33 gang members and established a “safety zone” within which gang members were prohibited from engaging in specific public behaviors (e.g., congregating, wearing gang clothing, using graffiti, intimidating others). By 2020, following a statewide review and lawsuits over gang databases and injunctions, many of California’s gang injunctions were scaled back or dropped — including in Oxnard.

Albeit, gang injunctions are not laws on gangs, the injunctions acted like civil court restraining orders for street gangs. The Oxnard injunctions against Colonia Chiques and Southside Chiques were highly effective. Critics claimed they were unfair, but the decrease in crime told the truth. To learn more see the blog Southside Chiques: A Violent Neighborhood.

Two Federal Laws That Could Work if Used

Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. Federal law 18 U.S.C. 521 (Criminal Street Gangs), for instance, enhances penalties for crimes committed in furtherance of a gang. But in Los Angeles, the U.S. Attorney’s Office rarely applied it.

Congress passed the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970. The law targets organized crime, especially the mafia, by making it a crime to:

- Belong to an enterprise that commits a pattern of racketeering activity (e.g., drug trafficking, extortion, murder)

- Use proceeds from such crimes to operate or acquire an enterprise

The U.S. federal government created the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) to combat organized crime by targeting individuals and entities involved in ongoing criminal activities. RICO—18 U.S.C. 1961 is supposedly a cornerstone of federal gang prosecutions. The truth is, despite having one of the strongest laws on gangs, federal prosecutors often lack the will to apply it. In 2000, thirty years after Congress passed the law, the Los Angeles U.S. Attorney’s Office had filed only three RICO charges.

Gun Charges Try to go Federal

If investigators discovered a gang member—previously convicted of a felony—in possession of a firearm, they could charge him locally under California Penal Code section 12021(A)(1), Felon in Possession of a Firearm. The risk of local prosecution (particularly in California) is a slap on the wrist, federally the gang member is looking at 4 years in federal prison as opposed to 3 months in state custody.

Ping Orders Try to go Local

Trying to local a gang member use a “ping order”. Starting around 2007, federal ping orders from a judge determined a phone’s location by requesting the cell phone provider to transmit a signal to the device and receive back location data, typically through cell tower triangulation.

Ping orders were another frustration. Local DA’s offices could obtain them within hours. Federally, it could take weeks. One Deputy U.S. Marshal in Los Angeles told me his office had stopped requesting federal pings altogether. That kind of bureaucratic delay undermines real-time enforcement.

Wiretaps Try to go Local

Want to hear what gang members are saying, get a wiretap. A wiretap is the practice of connecting a listening device to a telephone line to secretly monitor a conversation. Wiretaps told the same story. Federal prosecutors made them cumbersome, time-consuming, and discouraged agents from using them. Local wiretaps have less reporting requirements and going up on other lines is much easier. Unfortunately in Los Angeles the federal prosecutors refused to use evidence from local wiretaps for federal cases.

Inconsistent Application of Laws on Gangs

In 1988, the California State Legislator passed the Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act (STEP Act) to combat gang activity.

California gang law Penal Code 186.22(a) made it a crime to actively participate in a street gang. While the Ventura County Sheriffs Office in Thousand Oaks applied it aggressively against the 68 members of the Tocas gang, the Santa Paula Police Department didn’t. The Sheriffs Office had arrested the Tocas with 130 violations of PC 186.22(a), compared to just 38 charges filed against the 67 members of the Crimies. The result? Such disparities in enforcement undermine the deterrent effect that laws on gangs are intended to create.

6 Ideal Laws to End Gangs

Federal

- Gang membership/affiliation should be a deportable offense, currently it is not.

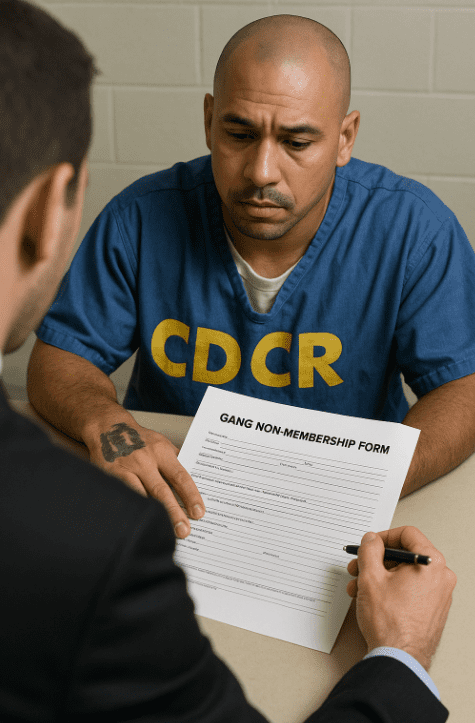

- There should be a law discouraging prison gang membership.

All prison gang members would be offered an opportunity to be rehabilitated by renouncing their prison gang membership by signing a a non-membership form, under penalty of perjury.

The non-membership form would be a contract between the prison and prisoner. By signing the non-membership agreement the prisoner swore not to participate, help, promote, or assist any prison gang like La Eme. For example, promote the gang would be violated if a prisoner got additional gang tattoos. In addition, investigators could use seized gang lists, cell phones, and kites (paper messages) could be used to determine if a prisoner participated or helped the gang.

All gang members who refused to sign or violated the terms of the non-membership form would receive an additional 5 years in prison. Failure to sign the non-membership form or a contract violation would authorize the prison to seize money on the prisoner’s books.

Every thirty days the non-signing prisoner would be offered the opportunity to sign the non-membership form. Every time the prisoner refused the first step at rehabilitation by not signing the non-membership form, privileges could be taken away. Some examples of privileges are: purchase items through the commissary, visitation rights, exercise, conjugal visits, etc. The whole idea is to convince the prisoner that gang membership is not worth it.

Any prisoner who signed the non-membership form would receive free tattoo removal. To learn more about prison gangs see the blog La Eme.

State

3. States should make possession and/or use of a cell phone in jail or prison a felony.

Cell phones in State jails and prisons are a serious problem however, prisoners caught only face a misdemeanor.

A possible solution to gang members or any prisoner using unauthorized cell phones and social media could be a law that would make it a felony punishable by an additional two years in custody and up to $10,000 fine. This would be an easy crime to prove. For instance, social media communication between the inmate and the gang member could serve as evidence. Likewise, a recorded conversation from a wiretap would also prove the violation.

4. A law should exist to make joining a gang a crime. At present, there are no statutes that deter voluntary gang membership—only laws that address coercion or recruitment. Yet interviews with gang members consistently reveal that joining is almost always a voluntary decision.

The legal system criminalizes affiliation with international terrorist organizations, but not with domestic groups that function as criminal street gangs and often operate like terrorist organizations at the community level. An ideal law would fill this gap by targeting specific, provable acts of affiliation—such as participation in initiation rites or documented arrests alongside validated gang members—while imposing graduated penalties that balance deterrence with constitutional protections.

Local

5. A law could discourage gang membership by making it a condition for receiving food stamps or welfare.

In 2013–2014, 57% of the Santa Paula gang the Crimies received government aid. There should be a law tied to food stamps/welfare that would deter gang membership.

Gang members, should be required to sign a form/contract to receive aid under penalty of perjury swearing that the gang member would no longer participate, promote, or further the activities of the gang, or communicate with other known gang members. If a gang member violated this agreement, then they would be disqualified from collecting food stamps or welfare for five years.

If the police witnessed gang members hanging out with other gang members or if a cell phone/social media of a gang member had other gang member texts and phone contacts, they could be shown to have violated the law.

6. Enforce Building Codes

Building code enforcement. Many gang members lived in converted garages. After probation sweeps, it would have been ideal if we could notify local code enforcement, and illegal/dangerous structures were cited. To learn more about gang suppression see the blog What to Do About Gangs: A Street-Level Perspective.

Final Thoughts on Laws on Gangs

To make a real impact on gang violence, the government must first understand the street-level reality. Laws on gangs are only as effective as the people enforcing them. Judges must understand the danger gang members pose. Prosecutors must have the will to act. Agents/detectives must have tools that work—like fast ping orders and wire taps, flexible charging statutes, and reliable collaboration with law enforcement.

The takeaway is simple: federal adoption of felon-in-possession cases works. Federal RICO cases do not. In comparison, local ping orders and wiretaps are faster and more effective than their federal counterparts. Ghost guns can be prosecuted using ammunition statutes. Ultimately, gang injunctions save lives—even if some activists disagree.

The goal of laws on gangs is public safety, not philosophical debate. In practice, when applied correctly, these laws protect communities, reduce violence, and remove dangerous individuals from our streets.

To learn more about laws on gangs, get the book Less Tagging More Killing: