Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity That Defines Oxnard’s Most Violent Gang

September 3, 2025

When people talk about gang problems in Ventura County, one name inevitably comes up: the Surtown Chiques. This gang has been a persistent source of violence, drug trafficking, and law enforcement challenges in the city of Oxnard. Based on firsthand investigations and detailed analysis, the scope of the Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity demonstrates how entrenched gang culture can destabilize a community, overwhelm the courts, and cost taxpayers millions. To see where Surtown Chiques ranks read the blog Top 10 Most Dangerous Gangs in Ventura County.

The Size and Scope of the Gang

The Surtown Chiques are the fourth largest gang in Oxnard, with 62 documented members. On paper, that might not seem overwhelming, but the statistics tell a different story. Together, these 62 individuals have amassed 1,191 arrests—an average of 19 arrests per member. One individual in particular stands out: a single gang member has been arrested 65 times, showing a revolving door of crime and incarceration. I’ve analyzed hundreds of gang members’ criminal histories during my FBI career. The Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity numbers stand out even among hardened criminals. To learn more read the blog Gang Related Crime Statistics.

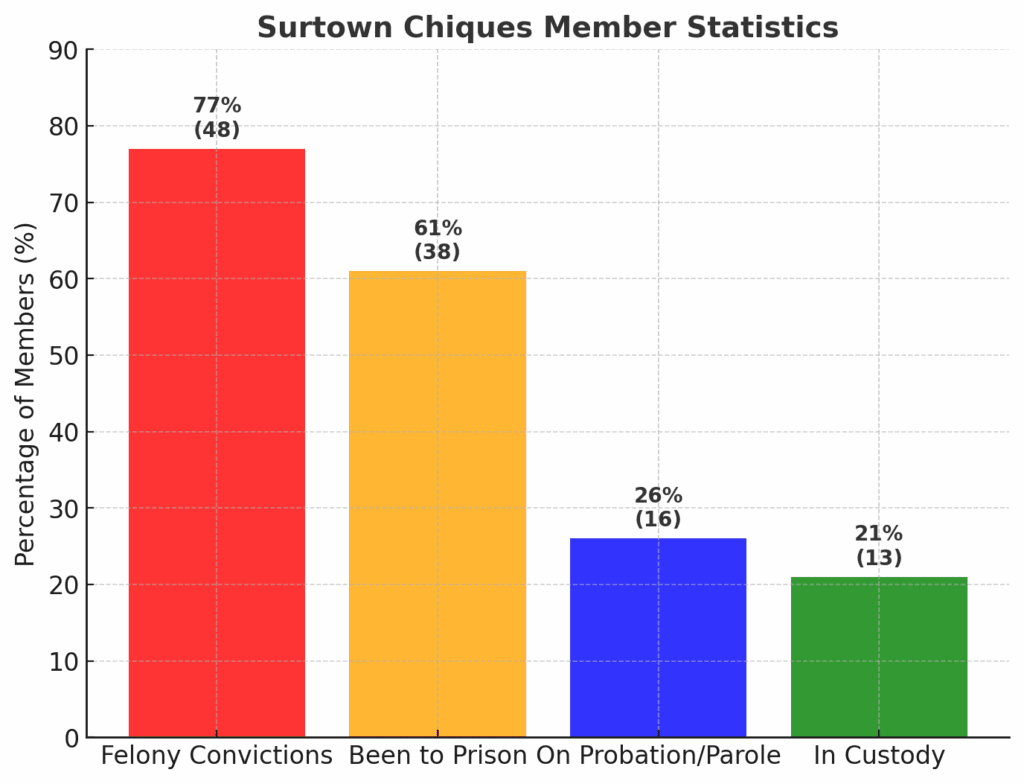

When we break down the criminal records of this group, the numbers illustrate the depth of the Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity:

- 77% (48 members) have felony convictions.

- 61% (38 members) have been to prison.

- 26% (16 members) were on probation or parole.

- 21% (13 members) were in state or federal custody at the same time.

These numbers highlight how the Surtown Chiques are not just a neighborhood nuisance—they are a full-fledged criminal enterprise contributing to violence and instability in Oxnard.

Gang members monikers include: Baby Snakes, Bouncer, Casper, Chubs, Cisco, Clumsy, Criminal, Daps, Downer, Gangster, Grims, Grusm, Huero, Lefty, Klepto, Lil Spooks, Lil Boo Boo, Lil Spanky, Lil Violent, Listo, Malo, Manos, Midget, Pequeno, Pranks, Rowdy, Scar, Shadow, Snags, Sniper, Spooks, Stomps, Stoney, Teaser, Tokes, Trigger, Trouble, Villain, Wyno, and Ziggy. To learn more about gang names read the blog Gang Names: Understanding the Criminal Identity System.

Territory and Graffiti

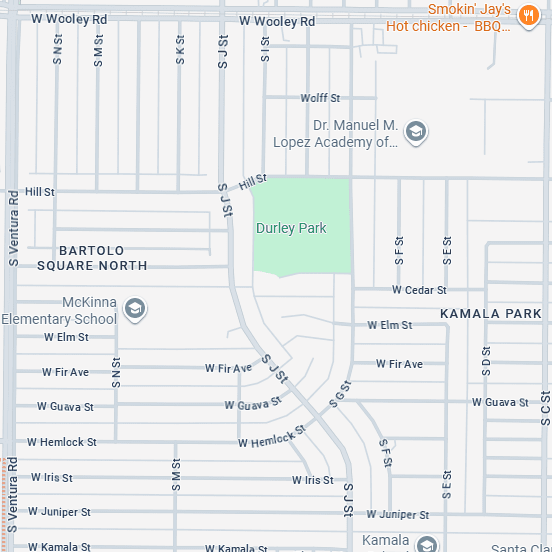

The Surtown Chiques gang “own” sections of the city of Oxnard to include south of West Wooley Road, east of Ventura Boulevard, north of West Kamala Street, and east of South C Street. The gang’s members frequent Durley Park.

The Surtown Chiques graffiti informs other gangs and residents that the defaced areas are “controlled and inhabited” by Surtown Chiques, meaning that Surtown Chiques members are allowed to sell drugs and “hand out” in this territory claimed by Surtown Chiques. In sum, the graffiti, typically consists of the letters “STXCH” or “SURXTOWN” which creates an atmosphere of fear and intimidation in the community.

Surtown Chiques rivals include the largest gang in the city of Oxnard, Colonia Chiques. To learn more about Oxnard gangs read the blog Oxnard Colonia Chiques. To learn about an Oxnard gang within Surtown Chiques gang territory read the blog Gangs and Ghost Guns: The Deadly Intersection of the Loma Flats Gang and Law Enforcement. The following map depicts Surtown Chiques territory.

Violence and Reputation

Several Oxnard Police Department detectives have told me that the Surtown Chiques are considered the most violent and dangerous gang in the city. That is a strong statement in a region already plagued by Sureno gangs aligned under the Mexican Mafia umbrella. The violence is not random but tied to drug trafficking, territorial disputes, and a culture that values retaliation over resolution. To learn more read the blog Gangs and Violence.

The Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity has consistently escalated to the point where both local and federal law enforcement have been forced to step in.

A Federal Trial

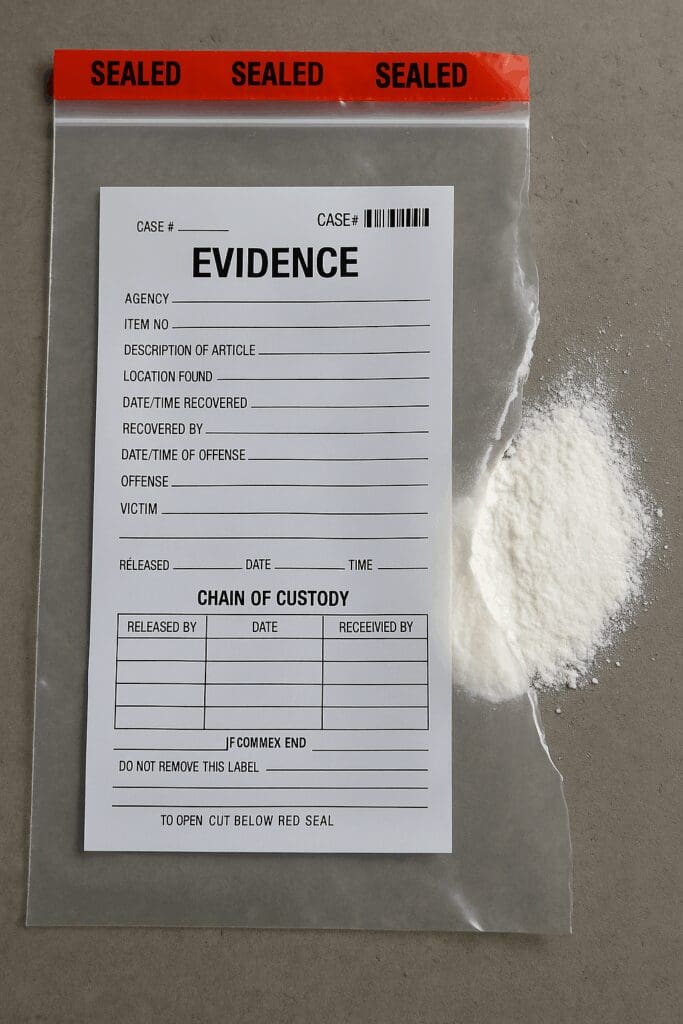

In 2019, I had to prepare for a federal trial involving a Surtown Chiques gang member accused of selling methamphetamine. This was not his first encounter with the system—he was already on his third defense attorney. The latest attorney requested an independent laboratory retest the methamphetamine involved in the case. A federal judge agreed, despite the fact that the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) laboratory results had always been reliable.

At first, this seemed like a complete waste of taxpayer money, since these independent retests rarely yield different results. I asked the independent technician how many times he had done independent retests.

His answer: nine cases.

When I followed up, asking if any of the results were ever different from the DEA’s, his response was simple: “None.”

The Methamphetamine Spill

The independent retest turned into an almost comical disaster. My partner and I brought the methamphetamine evidence from the vault to an FBI office break room so the independent lab employee could take his samples. While opening one of the baggies, he spilled a pile of white meth onto his gray pants. We both froze, realizing that mishandling narcotics in a federal building was not exactly in the training manual.

As he stood up, the meth fell to the floor. We attempted to sweep it up, but of course the sweepings contained dirt and even a hair. Ironically, when we weighed the meth back on the scale, it came out heavier than before.

Eventually, the retest results came back exactly the same as the DEA’s original findings. The whole exercise had cost thousands of taxpayer dollars, wasted hours of manpower. This was the kind of absurdity that sometimes accompanied the prosecution of Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity.

The True Cost of Gang Violence

The financial impact of Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity extends far beyond arrest costs. With 1,191 total arrests at roughly $1,000 per arrest, direct law enforcement costs exceed $1.1 million. But that’s just the beginning.

Court costs, public defender fees, parole/probation supervision, and incarceration expenses multiply those numbers. When gang members are on parole, supervision costs $10,000 per year. Federal prison costs $40,000 per year. California prison costs $131,000 annually per inmate. The 13 Surtown Chiques gang members in custody cost taxpayers over $1 million per year.

The Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity financial burden likely exceeds $3 million annually when you factor in healthcare costs from gang violence, property damage, and lost economic development in affected neighborhoods.

These aren’t just statistics. They represent taxpayer money diverted from schools, infrastructure, and community programs to deal with career criminals who refuse to change.

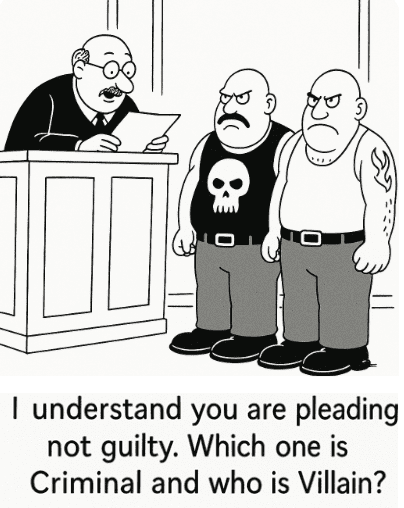

Criminal and Villain go to Federal Prison

The Surtown Chiques gang member “Criminal” was convicted at the conclusion of a four-day trial in September 2019 of conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine and five counts of meth distribution. In February 2020, he was sentenced to 13 1/2 years in federal prison. Prosecutors argued that he was more than just a street dealer—he was a key figure in a broader Mexican Mafia enterprise, attempting to dominate drug trafficking in Ventura County while extorting “taxes” from local gangs on behalf of EME. “Criminal’s” co-conspirator “Villain”, decided to plead guilty and was sentenced to over 11 years in federal prison. To learn more about gangs and drugs read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Surtown Chiques were not acting alone. They were plugged into a larger network of Mexican Mafia influence, where local gangs controlled street-level drug sales while funneling profits back to prison leaders. To learn more read the blog La Eme: Mexican Mafia Control Over California Gangs.

Community Impact

The violent presence of the Surtown Chiques does not only affect rival gangs or law enforcement. Ordinary residents of Oxnard live under the shadow of their activity. Families fear stray bullets. Businesses suffer from crime. Youth are recruited into gang life, enticed by the promise of belonging and protection, only to end up with lengthy rap sheets before their 21st birthdays.

This is why understanding the depth of the Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity is critical for policymakers, law enforcement, and the community at large. It is not just about statistics—it is about the erosion of safety and trust in neighborhoods where families should feel secure.

Conclusion

The story of the Surtown Chiques is not just about one gang—it is a window into how gangs operate, survive, and adapt in modern America. With 62 members responsible for nearly 1,200 arrests, their footprint on the criminal justice system is enormous. Their reputation for violence makes them one of the most feared gangs in Oxnard. Their ties to the Mexican Mafia elevate them from a local menace to a regional threat.

Until communities, law enforcement, and policymakers develop more comprehensive strategies, the cycle will continue. The Surtown Chiques: Gang Activity will remain a case study in how crime, cost, and bureaucracy collide in America’s fight against gangs.

To learn more about the Surtown Chiques gang, get the book Less Tagging More Killing.