Women in Gangs: Roles, Risks, and Realities

February 1, 2026

The world of gangs is overwhelmingly male, but ignoring the role of women in gangs misses critical dimensions of how these groups function. From Oxnard to Santa Paula and across the country, women navigate a contradictory space: essential for logistics and family continuity yet marginalized, exploited, and frequently dismissed as “drama.” Drawing from first-hand accounts in Less Tagging More Killing, this post examines the roles women occupy, the risks they face, and the realities they cannot escape within gangs.

The Language of Sexism

Gang culture is deeply sexist. Members often reduce women to slurs—calling them “hood rats,” “pin cushions,” or “rachets.” Each insult carries contempt: “hood rat” for promiscuity, “pin cushion” to mean “slut,” and “rachet” to mock a woman as “ghetto fabulous” when she is actually poor. Such language shows how women are objectified and disrespected within this subculture.

The irony is that while men demean women, they rely heavily on them. Mothers and girlfriends transport drugs, hold cash, and conceal weapons. They become critical links in the gang’s ability to operate, even as they are treated as expendable.

The following are female gang names: Cece, Cheeks, Lil Blunt, Piggy, Red, Vamps, and Vicious. To learn more read the blog Gang Names: Understanding the Criminal Identity System.

“School Runs” and Generational Cycles

I once observed a surreal scene that revealed the hidden family dynamic of women in gangs. Outside a gang member’s house—already swarming with police cars—several women drove up, each dropping off or picking up children with backpacks. I asked the gang member what was happening.

He replied, “My kids are going to school, and their moms are picking them up or dropping them off.”

I asked, “How many kids do you have?”

He hesitated, then counted: “Seven, no wait, eight, yeah eight.”

Each child had a different mother, except for two who shared one. None of the women seemed disturbed by the flashing lights or officers in the yard; it was as if gang arrests were part of the morning routine. When I asked about finances, the gang member admitted the mothers worked, while he lived off food stamps and whatever income crime provided.

This scene underscores the generational problem. Many children of women in gangs grow up around normalized violence, police presence, and economic instability. For the gang member, fatherhood was casual. For the women, parenting occurred under constant gang influence. Society bore multiplied costs—both financially and in future crime cycles.

Criminal Behavior and Gender Lines

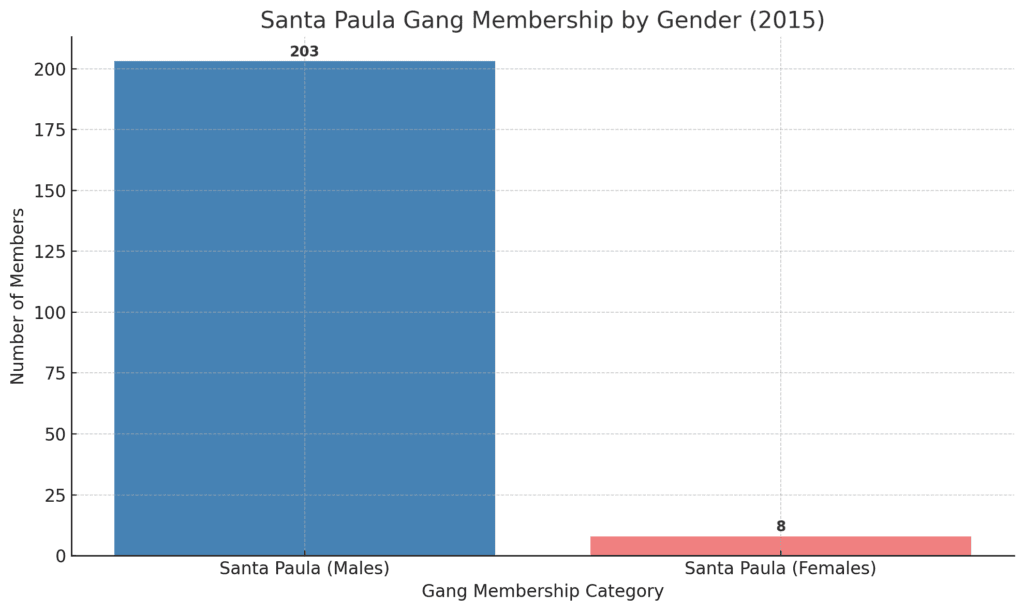

Criminal behavior remains primarily male. Women are rarely the heavy hitters; in 2015, of the 211 documented Santa Paula gang members, about eight—or 4%—were female. Yet those few were important. Women in gangs often transported drugs, hid firearms, and served as lookouts. Some were “jumped in” through initiation beatings like the men. Several of the female gang members were “sexed in” or “crimed in” by participating in crime on behalf of the gang. Others became associates through relationships. To learn more read the blog Gang Initiation for Females: Brutal Truths Revealed.

But their involvement created complications. As one gang member explained, “The female members create drama by having sex with members of the gang and members of other gangs.” Romantic entanglements often escalated into confrontations, sometimes culminating in shootings. Far from being neutral players, women in gangs could destabilize fragile truces or fuel rivalries.

The EME Barrier

At higher levels, women are excluded entirely. The prison gang the Mexican Mafia (La EME) sets strict membership requirements: you must be a Southern California Hispanic male, nominated by a member, and approved by three votes. Women are barred. As a result, this reflects the patriarchal structure of the underworld—men monopolize ultimate power, while women provide support but never hold rank. The irony is the male members often trust females with the money earned inside prison. To learn more read the blog La Eme: Mexican Mafia Control Over California Gangs.

Flop Houses and Female Associates

Female involvement often appears in the form of flop houses—drug-den residences that destabilize entire neighborhoods. In South Oxnard, a duplex rented by a drug addict became a staging ground for violence. He allowed a female associate of the Northside Chiques to sell drugs there. Southside Chiques noticed, and fights escalated to shootings. In one explosive moment, she took the high ground—an upstairs window—and opened fire on her rivals.

When police entered, the duplex was destroyed: graffiti covered walls, garbage and mattresses filled bedrooms, and the structure reeked of neglect. Later, before a search warrant could be served, gang members torched the building. Here, a female’s attempt to operate in rival territory triggered chaos, underscoring how women in gangs can become flashpoints in territorial disputes. To learn more about gangs and drugs read the blog Gangs Drugs: A Glimpse Into the Underground Economy of Crime.

Women and the Courts

Courtrooms are not immune to gang influence. I recall one incident in Ventura County where a young female associate of a Santa Paula gang nervously attended a trial. Deputies discovered she had affixed her cell phone to record testimony of a cooperating witness. Her plan was to deliver the recording to gang members, exposing the “rat.” This highlights another role for women in gangs: surveillance and intimidation. Even without holding guns, women could endanger lives by helping identify cooperators.

Hiding Weapons and Everyday Risks

Women also use their domestic roles to shield contraband. In Los Angeles, an FBI agent discovered a pistol hidden inside a stuffed animal during a search warrant. The stitching was neat, far better than the gang member’s admitted skills. The conclusion was obvious: his girlfriend had sewed the gun inside. This kind of concealment is common; law enforcement often finds drugs or firearms hidden in children’s toys, cribs, or diaper bags managed by women in gangs. To learn more about gangs and guns see the blog Guns and Gangs: A Deadly Combination.

Jailhouse Dynamics

Even in custody, gender plays a role. Female inmates sometimes mocked or cat-called deputies. Once, a female gang member held out a handmade flower crafted from toilet paper, smiling with a silver front tooth. She told me, “I made this for you, and I’m a virgin.” The claim was dubious, but the behavior reflected the manipulative tactics women in gangs adopt.

Risks and Victimization

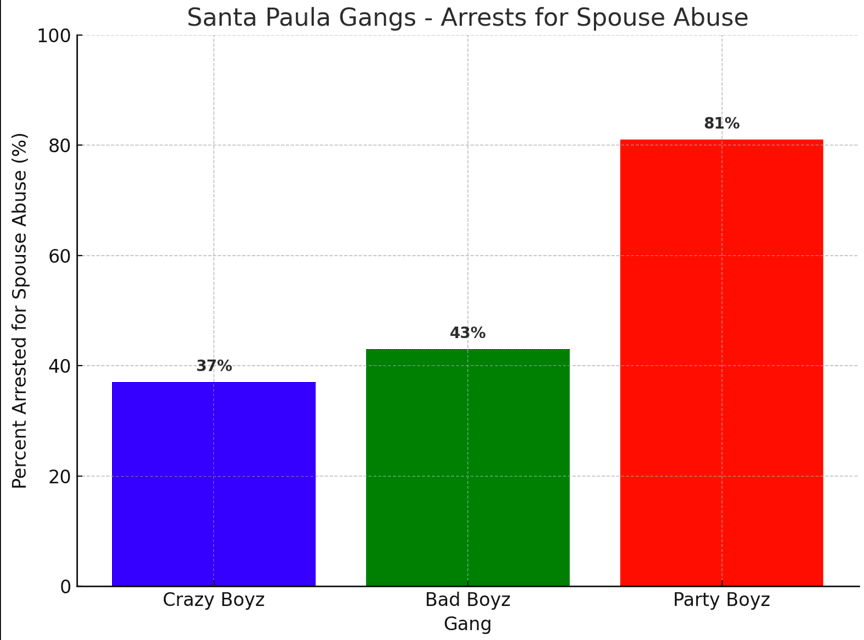

Domestic violence is a common crime for gang members. The 68 members of the Santa Paula gang the Crimies, had 50 arrests for spouse abuse/domestic violence. Consider the amount of domestic violence suffered by woman who associate with gangs. See the chart below for three other Santa Paula gangs arrests for spouse abuse:

Beyond their active roles, women also face higher risks of victimization. Many suffer intimate partner violence, sexual exploitation, or coercion into crimes. They often lack real protection from the crews that claim to “look after” them. National research confirms that women involved in gangs experience disproportionate trauma—coercive sex and threats from rivals or their own partners. In this way, women in gangs endure a dual reality: participants and victims of crime. To learn more read the blog Gang Related Crime Statistics: Trends and Analysis.

Exit Strategies: Few and Fragile

For men, exit often comes with prison or aging out. For women, pregnancy has been cited as an off-ramp, though research shows this isn’t always causal. Sometimes leaving the gang precedes pregnancy, not the other way around. Other exits include relocation, religious conversion, or intervention from family.

Conclusion

The picture of women in gangs is not uniform. Some drive cars for school drop-offs while ignoring police lights. Others smuggle guns in stuffed animals or record witnesses in courtrooms. Still others sell drugs and live in flop houses that destabilize neighborhoods.

Understanding women in gangs requires holding both truths: they are participants in crime, but they are also victims of sexist structures and coercive partners. There are fewer female gang members, so law enforcement training often overlooks their unique roles and participation.

Only by recognizing these realities can law enforcement, policymakers, and communities hope to break the cycle—for the men, for the women in gangs, and most importantly, for the children caught in between.

To learn more about women in gangs get the book Less Tagging More Killing.